This isn’t just about fossil fuels. It’s about something MUCH bigger

If you think the debate on ending fossil fuels is simple, try for a moment to see how this all looks to poorer nations

As I write this, the latest COP summit is nearing its conclusion in Dubai and the main sticking point comes back to the language on fossil fuels.

In short, many developed economies (and some developing nations, especially small island states) are pushing for the inclusion, in the language of the final statement, of a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. To most of these nations, the situation is maddening.

Everyone knows that to be in with a shot of achieving net zero carbon emissions we need to bring down the rate at which we’re burning them around the world. So why on earth is anyone objecting? It is, scream some, so simple.

And so if anyone’s fighting this glaringly obvious truth then there’s only one plausible explanation: they must be in the pocket of the fossil fuel industry, right? And that certainly explains some of the objections, not least for countries like Saudi Arabia. It’s a convenient narrative and has at least some truth to it.

But as it happens, no: this is not quite as simple as some people would have you believe. In fact it’s desperately complex. I should say at this point that, like George, I’m very much in the getting-rid-of-fossil-fuels camp (albeit that having written Material World I’m in little doubt about how difficult that will be). But I’m also very worried that we’re ignoring something incredibly important: the ability of poor countries to increase their access to energy.

You see, there’s a reason why it’s not just Saudi and other oil producers who are fighting the “phase out fossil fuel” ambition. Western newspapers often ignore this, but alongside Saudi are China, India and Brazil. Now, given Brazil has a large and growing petrochemical sector one could lazily dismiss them as another fossil fuel apologist, but then what about China? What about India? That brings us to the nub of the matter. Enormous energy inequality.

One of the things I wrote about in Material World, and covered in a previous post, was the idea that one useful way of looking at the world was via the prism of steel use. We in the developed world have about 15 tonnes of steel per capita, in all the cars, hospitals, transport infrastructure and so on that surrounds us. But those in sub-Saharan Africa have less than one tonne per capita.

This steel inequality is a really good way of understanding the gap in living standards between nations. You can’t build a hospital or a train network without steel - and so this steel inequality is a useful measure of the gap in living standards between nations. And if sub-Saharan Africa is to get to western levels of steel per capita then that means we have to make a lot more virgin steel, and there’s no cheap way of doing that without enormous carbon emissions.

But you can do the same exercise with copper. You can do the same thing with oil per capita. In each case you find a massive gulf between rich and poor nations. Why? Because our living standards are in large part a function of the stuff we have around us. That’s the inexorable logic of living in this “Material World”.

Perhaps the most all encompassing way of seeing this is by comparing different countries and regions in terms of their energy usage per capita.

Again, if you’ve read the book you’ll know it’s as much about energy as about materials. Everything in economics is energy; a lesson we are only vaguely internalising post-Ukraine. Doing pretty much anything involves the deployment of energy; so rich countries tend to be far, far more energy intensive than poor ones. And as nations get richer they get more energy intensive.

Here’s what I wrote on page 317:

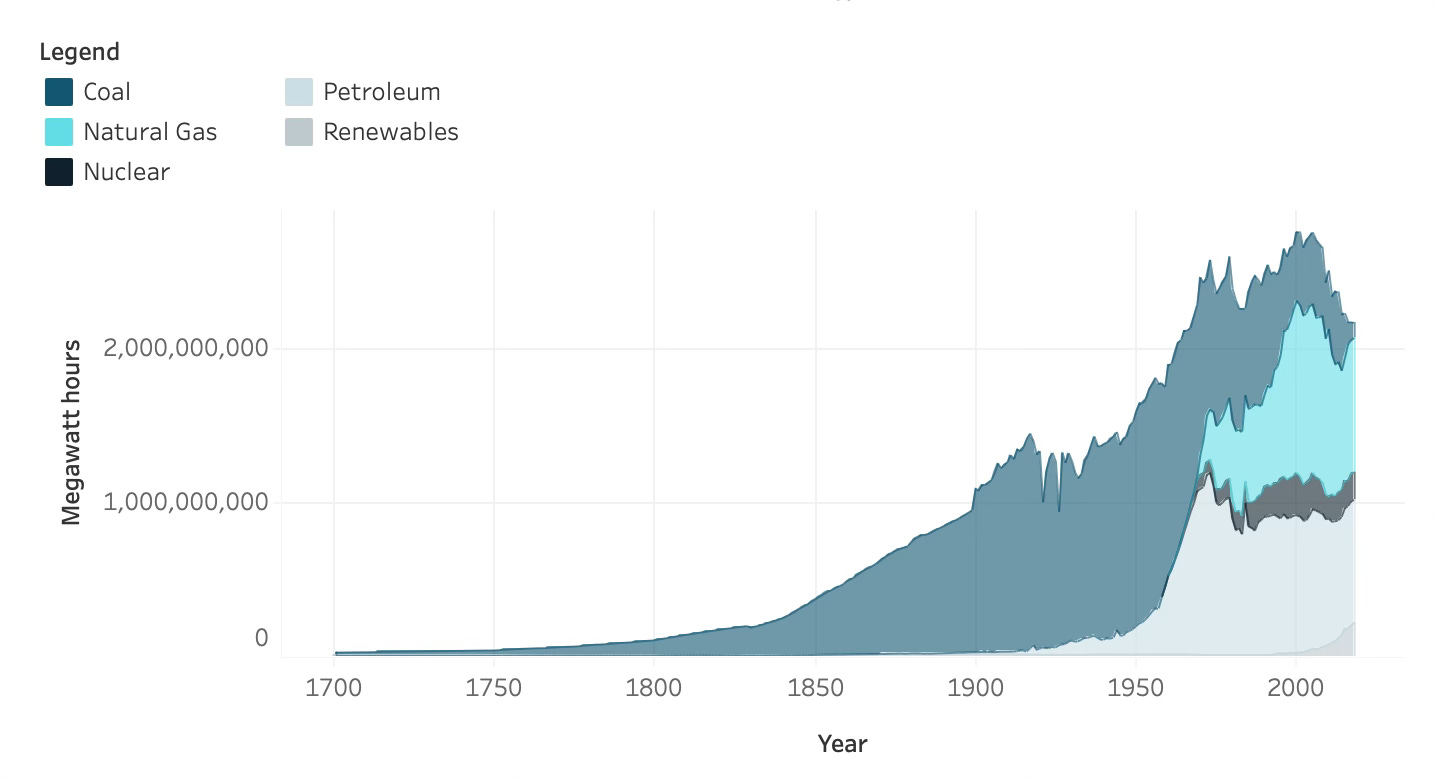

The industrial revolution was not just a revolution of ideas and engineering and chemistry; it was an energy revolution. The vast majority of processes you have encountered in the preceding pages, from the transformation of sand into glass, through to the creation of silicon chips, the production of chlorine out of brine, the conversion of iron into steel and the generation of electricity, depends on enormous amounts of energy, most of which is currently delivered to us, directly or indirectly, by fossil fuels. The extraordinary explosion of wealth and wellbeing that began somewhere in the middle of the nineteenth century might better be seen as an extraordinary harnessing of these fuels to do stuff.

Look at Britain’s development - or for that matter the development of any major economy - and what you see is as it gets richer its energy consumption goes up almost in lockstep. It’s only in the past few decades that the relationship has broken down. Today the energy intensity of our GDP is actually falling - which is a good thing (though this is partly exacerbated by the fact that we’ve been deindustrialising in recent years, importing stuff from other countries who actually make things).

This relationship is not a coincidence. As I say: all economic activity is to a greater or lesser extent the deployment of energy. And in much the same way as there’s a massive inequality between rich nations and poor nations in their steel-per-capita, there’s a massive gap in their energy per capita too.

In energy per capita terms, many nations remain where Britain was in 1800 - at a primitive level of development where life is hard, lives are short and there simply isn’t enough energy to make stuff happen. This might seem baffling, but a useful thing to remember is that 85 per cent of people living on planet Earth have never been in an aeroplane.

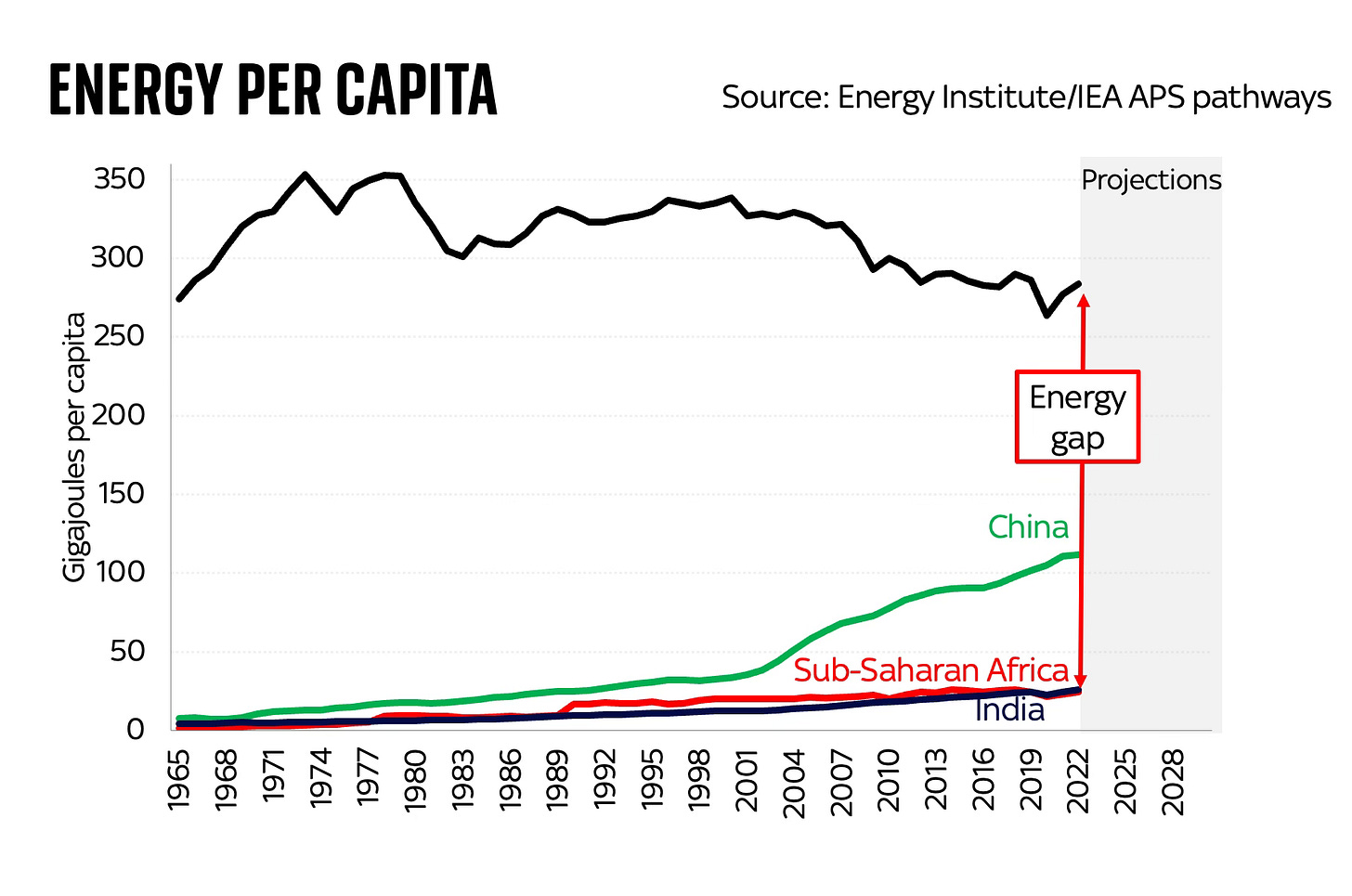

Anyway, below are the relevant figures from the Energy Institute dataset. You can see the massive gap between the US and India or Sub-Saharan Africa, and you can also see how China’s energy consumption has grown ever larger in recent years, as it has industrialised and become the world’s manufacturing powerhouse.

When you look at these charts a couple of things stick out. The US is incredibly high - and it’s worth noting that European energy consumption levels are actually now below China’s. But for me what sticks out most of all is how low the bottom countries are. In much the same way as their low steel per capita numbers underline poor development outcomes in sub-saharan Africa, these desperately low energy-per-capita numbers are a sign of this region’s poor standard of living.

Talk to anyone in India or China and the chances are it’ll be this they bemoan. They don’t want to decrease their energy-per-capita. They need to increase it enormously because they need more energy to enable them to do stuff. They need more steel so they can build more infrastructure. They need more cement so mud floors can be replaced with concrete ones. More copper so they can electrify their towns and settlements. More power lines. And so on and so forth. This all involves lots of energy consumption.

Which brings us back to fossil fuels and climate change. It might seem baffling to wise and well-meaning folks in London and New York that so many nations in the developing world are resisting any attempt to commit to this language. What on earth have they got to lose? Do they want to destroy the planet? Why are they fighting what’s self-evidently right?

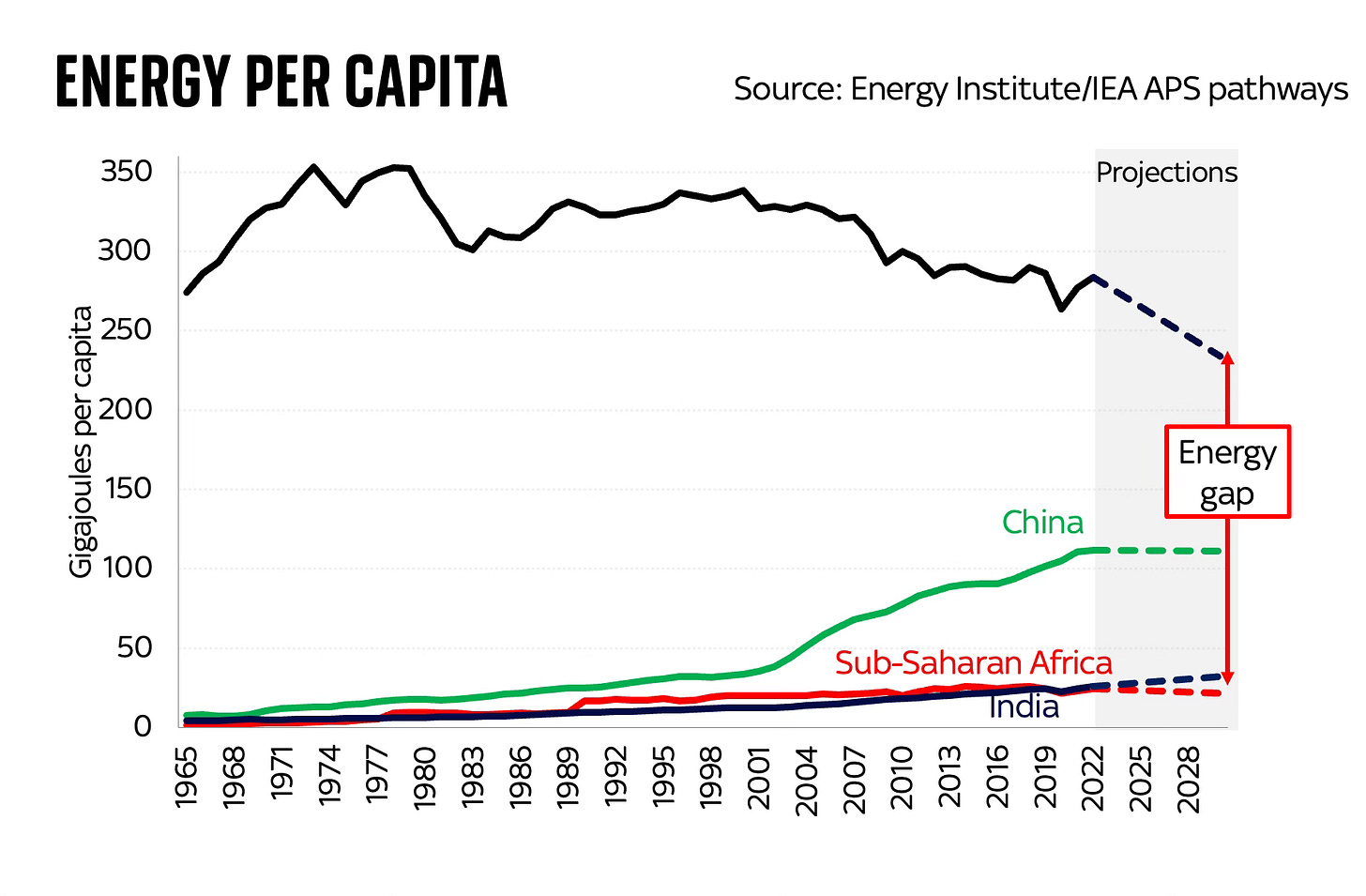

Well, for an idea, let’s consider what happens to those energy per capita figures if the world commits to the kind of pathways for climate change mapped out by institutions like the International Energy Agency. Look at what happens in the coming decade or so (the lines here are based on the IEA’s Net Zero report - the APS pathway).

You see the issue here. The lines converge somewhat but there’s still an enormous energy gap. Look at China: all of a sudden, it goes from being on an ever upwards pathway of energy consumption (and development) to flatlining. Are they ok with this? Erm, no.

For India and Sub-Saharan Africa it’s even worse. They languish, in energy per capita terms, way below everyone else, trapped seemingly permanently in a low energy world.

And here’s the thing. This chart isn’t a fossil fuel chart. It’s energy of all stripes, including (ever more in the future) green energy. It’s saying these nations and regions will be energy poor even if it’s green energy. And this is the developed world vision for net zero. It’s quite astounding.

Perhaps you’re starting to see how things look to those in the developing world. The rich world is essentially laying out pathways that would consign poorer countries to a permanent life of energy poverty, purely to make their sums add up.

Now, none of the above is to dispute that our attitude to fossil fuels matters - that we need to do everything we can to reduce our dependence on them and find more sustainable alternatives. It will be very tough to do so - far tougher than anyone fully understands. That’s one of the sub-plots of Material World.

But for many countries (which by the way have the majority of the world’s population), access to energy is far, far more important and a much more immediate concern. This might be desperately frustrating for those in rich nations who spend a lot of their time fretting about climate outcomes. But they need to respect it. At the moment they mostly prefer not to talk about it.

Indeed, at meetings like COP, so far rich nations haven’t given the developing world a clear sense of how they’re going to get that energy in future. While there’s been a bit of talk about providing some “loss and damage” money to compensate them for climate change impacts, the funds have hardly been forthcoming. Anyway, this ignores the elephant in the room - that enormous energy gap which, under most pathways for 2050 will become permanent.

It’s not inconceivable to see how this could be addressed. It’s possible to imagine a more just and fair transition, where rich nations commit to sending their technology - their batteries, their solar panels, their carbon capture units, to poorer nations. They could be committing to waiving the patents for important tech if it helps speed the transition (though there’s a question about whether that might dull the incentives to innovate). They could be promising to do everything they can to allow poorer countries to increase their energy consumption and (it’s the same thing) their standards of living.

But they’re not. And the reason they’re not is that they recognise that it would make the energy transition incredibly (perhaps prohibitively) expensive. Imagine, for one thing, how much it would cost if the rich world had to subsidise billions of tonnes of green steel production in the developing world (which is, after all, the only way we’ll allow them to get to our levels of steel-per-capita without spewing enormous amounts of carbon into the atmosphere). It would be astoundingly expensive. Now imagine this for every form of industrial production: chemicals, cement, metals refining. The total cost would run into the trillions of dollars.

And since rich nations are having enough difficulty keeping their citizens fully behind net zero even now, one can understand why they don’t want to unleash this can of worms. How much harder their efforts would get if they declared that their citizens will also be heavily taxed to subsidise those in other countries, to deliver the outcome they’ve promised (and told their citizens it would cost nothing).

So instead we see what we’ve seen in recent weeks. Rich nations lecturing everyone else (even as they continue to consume large quantities of fossil fuels themselves). Indeed, as I tried to explain in a thing I did for Sky News today, far from plateauing as laid out in the IEA’s net zero modelling, actually oil production is still rising. And in part that’s because we continue to use rather a lot of it.

Try to see how this looks from the perspective of the developing world. Many developing nations would dearly like to be able to shift from fossil fuels to other forms of energy, but for the time being coal and gas are simply the cheapest, easiest ways of providing the energy they need to try to narrow those gaps in the chart above. And why would they go along with a plan to rule out those fuels given those rich nations aren’t providing any support to allow them to do it - and given their previous promises of support haven’t actually been delivered?

So no: casting the fossil fuel phase out debate as a “simple” clash between nasty fossil fuel producers and virtuous north European nations isn’t right.

This isn’t good vs bad - much as we’d like it to be. It’s far more knotty than that. Nor is it just about fossil fuels or carbon. It’s also about energy and access to energy. And about whether the energy-rich have any right to commit billions of people to a lifetime of energy poverty.

Dear Ed - very much enjoyed the substack post. I agree... you are essentially echoing the 'Energy Cost of Energy' points made by Dr Tim Morgan, formerly of Tullett Prebon, in his 2013 report entitled Perfect Storm – "Energy, Finance and the End of Growth". You can find the report here: https://ftalphaville-cdn.ft.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Perfect-Storm-LR.pdf. It's worth re-reading.

And you are quite right that the developing world isn't going to stand for being forcibly deindustrialised. You'll have noticed that there is a strong minority also in the developed world that "disagrees with George"... my question to you is why are you "like George ... in the getting-rid-of-fossil-fuels" camp?

Perhaps the 'Like George' camp have missed what the developing worlds have realised, namely that

- the climate alarmists' prophesies of doom keep on not coming to pass

- the IPCC have substantially watered down their expectations regarding future warming, and the mainstream researchers agree that the ‘tipping point’ scaremongering (encapsulated by the long-out-of-date-but-gutter-press-favourite RCP8.5 pathway) of recent years was just embarrassing nonsense (https://gmd.copernicus.org/preprints/gmd-2023-176/).

- and the simplistic thesis that manmade CO2 might be "causing" material (!) climate change is looking increasingly shaky, and a cultish belief in this simplistic belief is looking more and more like a false religion. See more here: https://reaction.life/the-religion-of-climate-alarmism/.

I am quite aligned with Ambrose-Evans Pritchard in the Telegraph: “We no longer need the COP circus – technology and markets are already solving the climate crisis” (though I never saw it as a 'climate crisis' in the first place). See https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2023/12/05/cop28-circus-technology-markets-solve-climate-crisis/.

This is not the time to accelerate our path to deindustrialisation and pauperisation. Better to take stock, ensure we have energy security and reassess how far 'TheScience' has led us down a blind alley.

Excellent post. It is very easy for energy rich citizens of developed nations to talk about keeping fossil fuels in the ground where they belong as they move over well developed infrastructure, flip switches to have cheap heating or cooling, and run their modern technology while expecting citizens of poorer nations to be satisfied with living as if they were still in the 19th century. The utopians have great passion but little, if any, common sense or concern about the lives they are damaging with their pie in the sky plans.