Why are we erasing our industrial history?

Britain is littered with blue plaques commemorating where famous authors and politicians lived. Yet we happily demolish our most important industrial landmarks without marking them for posterity.

Did you know that Glasgow used to have the tallest chimney in the world?

Tennant’s Stalk, an enormous stack of bricks built at a massive chemicals plant in 1842, was for a period one of the tallest man-made structures on the planet. It towered over the city, establishing itself as one of the iconic landmarks of the city until it was struck by lightning and had to be dismantled.

Except that when you go to the St Rollox district where the chimney used to stand there is no evidence of it today. What used to be one of the world’s biggest manufacturing sites has been replaced with housing estates and road underpasses. There was supposedly a plaque commemorating the plant but when I went on the hunt for it last year it too seemed to have disappeared.

In one sense you can understand why many people in Glasgow were happy to erase this period of their history from the landscape and the collective consciousness. The plant beneath the chimney, which turned salt into various chemicals including bleach via a reaction known as the Leblanc Process, spewed so much sulphurous smoke into the city that it became a nationwide scandal. Indeed, the world’s first pollution laws were imposed to deal with the stuff coming out of that chimney and another even taller chimney built nearby soon afterwards. Perhaps they are best forgotten.

Even so, you can’t help but wonder about the somewhat arbitrary nature of which parts of our history we do and don’t erase. Why is it that we happily commemorate our history of steelmaking, iron production, textiles and even salt with museums and exhibits while other bits of our industrial history are allowed to disappear altogether?

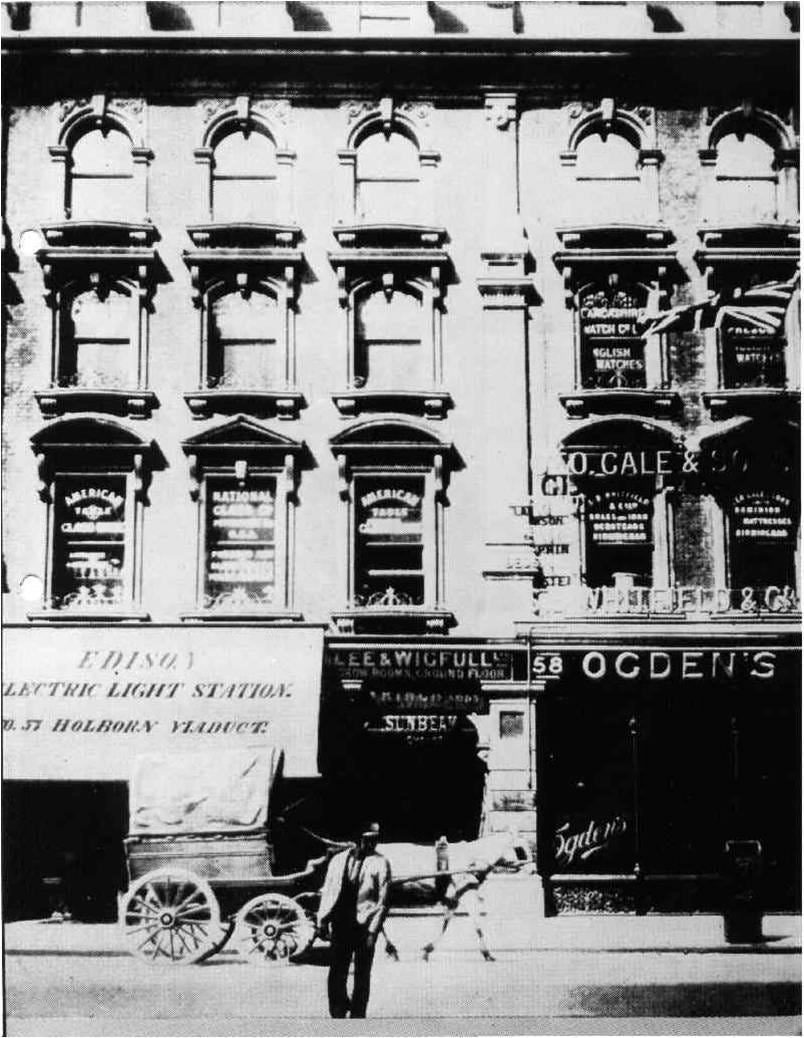

I’m not sure of the answer but the upshot is that a lot of fascinating episodes from our history get buried away. Did you know, for instance, that the world’s first coal-fired power station was on Holborn Viaduct in the heart of London? The Holborn power station, which narrowly predates Thomas Edison’s far more famous Pearl Street plant in New York, is surely one of the most important sites in modern history. This is where the electrical age began, for heaven’s sake!

Yet there is no evidence of this whatsoever in Holborn. It’s as if it never happened.

In the course of writing Material World I kept coming across examples like this: significant milestones in modern history whose memory seemed to have faded or even been physically erased. If you’ve read the book you may recall the difficulties I faced trying to find the building where the world’s most important plastic was invented. There is a blue plaque to commemorate it, but it’s barely visible these days.

And even as I write this, further pieces of Britain’s industrial history are being dismantled. In yesterday’s Sunday Times I wrote of the closure of the plant at Billingham which is one of the world’s longest-running Haber Bosch facilities. Given the production of nitrogen fertilisers is by some yardsticks the most important single industrial invention of the modern era and given this plant represents an important chapter in that story - both in the UK and internationally - you might have expected there would be outcry and consternation about this watershed moment. For the first time since this process was invented more than a century ago, these critical fertilisers will not be made in this country! Yet up until my column, the closure hadn’t even been reported in the mainstream media.

Nor is this the only piece of living industrial heritage nearing its demise. Next door to that Haber Bosch facility is another plant where ICI once made the perspex that went into the canopies of Spitfires. That unit, the Cassel works, is also being shut down by its current owners, Mitsubishi Chemical UK.

Now, there’s no point in getting nostalgic about places while ignoring the challenges that have led to their closure. The processes used at the Cassel works are pretty dirty and are far from the state-of-the-art. The Haber Bosch plant at Billingham consumes large amounts of natural gas to make its fertiliser, and that gas is now more expensive on this side of the Atlantic, so the ammonia it once produced will instead be shipped in from the US, where it will be made with fracked American gas. There is a logic to all of this - even if it raises serious questions about Britain’s increasing reliance on the rest of the world for critical chemicals.

But the general public’s general obliviousness about the history that’s crumpling at this very moment underlines how much we’ve lost touch with the Material World. We rely on this complex of processes and businesses to help keep us alive. Yet we pay it so little attention these days that barely anyone seems to notice when another of its most significant sites disappears.

What many these places represent in the inventive nature of our forefathers but seems to be sadly lacking today in the fact that despite the efforts of many in engineering and scientific institutions we still can't get young people seriously interested into entering these professions.

As an aside we are just over a year away from the closure of the last big coal station in the UK at Ratcliffe. The design here had progressed the generator size from Holborn by 5000 times and massively reduced the amount of coal that was burnt to achieve that output. Ratcliffe isn't particularly special there were dozens like it but like Billingham it becomes the last. It can't be saved as a museum unfortunately but will it be acknowledged for how it whirred away in the background since 1968 providing electricity to the UK grid,

Yes, history is important, including the notorious downsides sometimes still lurking in our soils and the silts of our rivers and estuaries. Will we increasingly rely on some of our legacy structures for a perforce less material and energy consuming world? The railway bridge over the Tweed at Berwick upon Tweed is still working, standing on the great imported pine piles that were hammered in by some of the first steam hammers. There is a small museum presentation in the station. And there are still 2000 miles of canals. 'Money' is a poor signal for perceiving wider utility or future value?