Time to talk about the Panama Canal

Apparently Donald Trump wants to bring it back under American control. Here's a crazier idea

When, the other day, Donald Trump signalled that he’s prepared to take back control of the Panama Canal, his remarks, on social media and at an event prompted predictable derision in many quarters.

Could there be a more preposterous idea?! Well, I’m here to tell you that: yes, there is a more preposterous idea. And I want to tell you about it. Because as preposterous ideas go, it’s actually quite interesting.

But before we get to my preposterous idea, first let’s talk about the president-elect’s. Because in some senses his comments aren’t quite as preposterous as some people are suggesting.

The Treaties of the Panama Canal

Trump’s beef goes back to 1977, and a treaty signed by the late Jimmy Carter. The 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaty pledged that Panama would gain control of the canal after 1999 - which was indeed what happened.

But the Carter treaty is best seen as a revision of another treaty, the original canal treaty which dates back to 1903 and gave the US a perpetual lease over the Panama Canal Zone, a six-mile zone surrounding the canal across the isthmus.

Panamanians were furious about this treaty from more or less the moment it was signed in late 1903 - and for good reason. It was done more or less at the barrel of a gun.

To see why, it’s helpful to begin the story in early 1903, some months before the treaty in question was signed. At this point, Panama was not an independent state but a province of Colombia.

The Americans, set on building the canal in Panama, had tried to negotiate yet another treaty (sorry, there are lots of treaties going on here) with a Colombian representative called Tomás Herrán. This precursor to the precursor to the Carter treaty had one critical difference: the Americans would get a one-hundred year lease on the canal - with the option of renewal.

Had this treaty been signed then - who knows? - perhaps there’s a parallel universe where America would have given up the canal in 2014 (a century after its completion) and maybe Panama would still be a part of Colombia. But what actually happened was that the Colombian senate refused to ratify the Hay–Herrán Treaty, disgusted with the idea of giving up control of some of their land.

This was, in hindsight, a terrible miscalculation, for a few months later they would lose control not just of the six miles surrounding the canal but the entire province of Panama. Because, furious about being rejected, America, under President Theodore Roosevelt, encouraged a local junta led by Manuel Amador, to secede from Colombia. Bunau-Varilla (we’ll get to why on earth a Frenchman was so involved in all this in a moment) wrote Amador a $100,000 cheque to fund the independence movement. By November, the rebels had declared independence in a bloodless coup (that it was bloodless owed at least something to the looming presence of American gunboats neaby).

Anyway, before the dust of the revolution had settled, Bunau-Varilla, who in return for his $100,000 cheque had promptly been appointed as Panamanian ambassador to the US (that he wasn’t Panamanian seemed not to be a problem), rapidly did a deal with the Americans. Together with US Secretary of State John Hay he drafted a newly-revised treaty for the canal. But this time there was one key difference versus the one the Americans had previously attempted to agree with the Colombians: instead of leasing the canal for 100 years, the American lease would be perpetual.

Naturally the newly-independent Panamanians were outraged. Why on earth should their first major diplomatic deal upon winning independence be to sacrifice the sovereignty of a key slice of their country? Well, the answer was: they were strong-armed into it. The best account of this is to be found in David McCullough’s magisterial history of the canal:

[Bunau-Varilla] sent a 370-word cable to Minister de la Espriella that struck an entirely new note of fear. If the government of Panama failed to ratify the treaty immediately upon the treaty’s arrival at Colón, then the almost certain consequence would be an immediate suspension of American protection over the new republic and the signing of a canal treaty with Bogotá.

The mention of Bogotá at the end is the key bit. If the Panamanians didn’t agree then America might turn back to the Colombians. The independence movement would be over - a few weeks after it began.

It was blackmail of the highest order. As far as anyone can work out, this threat came not from the White House but from Bunau-Varilla himself. As McCullough writes:

In any event, it was the ultimate knife at the throat and wholly spurious. The notion that Roosevelt would abandon Panama at this point, that he would leave the junta to the vengeance of Colombia, that he would now suddenly turn around and treat with Bogotá, was not simply without foundation, but ridiculous to anyone the least familiar with the man or the prevailing temper in Washington. Nothing of the kind was ever even remotely contemplated at the White House or the State Department. “This time I hit the mark,” Bunau-Varilla was to exclaim. “The Government of Panama was at last liberated from the morbid influence of its delegation.”

So, thanks to the perfidy of their French ambassador to Washington, Panama signed the treaty and the rest is history. America got its perpetual lease. Panama got its independence. And the festering wound of the Canal Zone continued until the 1970s, when it was finally lanced by Jimmy Carter.

But Republicans have been dismayed by what they see as Carter’s treachery ever since. They believe that since the canal was built by American workers (many of whom laid down their lives) and would never have happened without American capital, the country should continue to control the canal.

The fact that fees for passage (which American vessels had to pay due to another treaty - the Hay–Pauncefote Treaty - but I think by now we’ve all had enough of treaties haven’t we) have risen so much in recent years is a further insult. All of which brings us to the president-elect’s comments. Preposterous they might seem, but they are rooted in a historical story which goes back a long way.

The (French) Back Story

Indeed, in some respects, this story goes back even further. Why, you’re probably wondering, was a Frenchman intimately involved in this treaty - a treaty Donald Trump would rather like to reinstate? Because the whole reason the canal came to be there in the first place was thanks not to the Americans, but to the French.

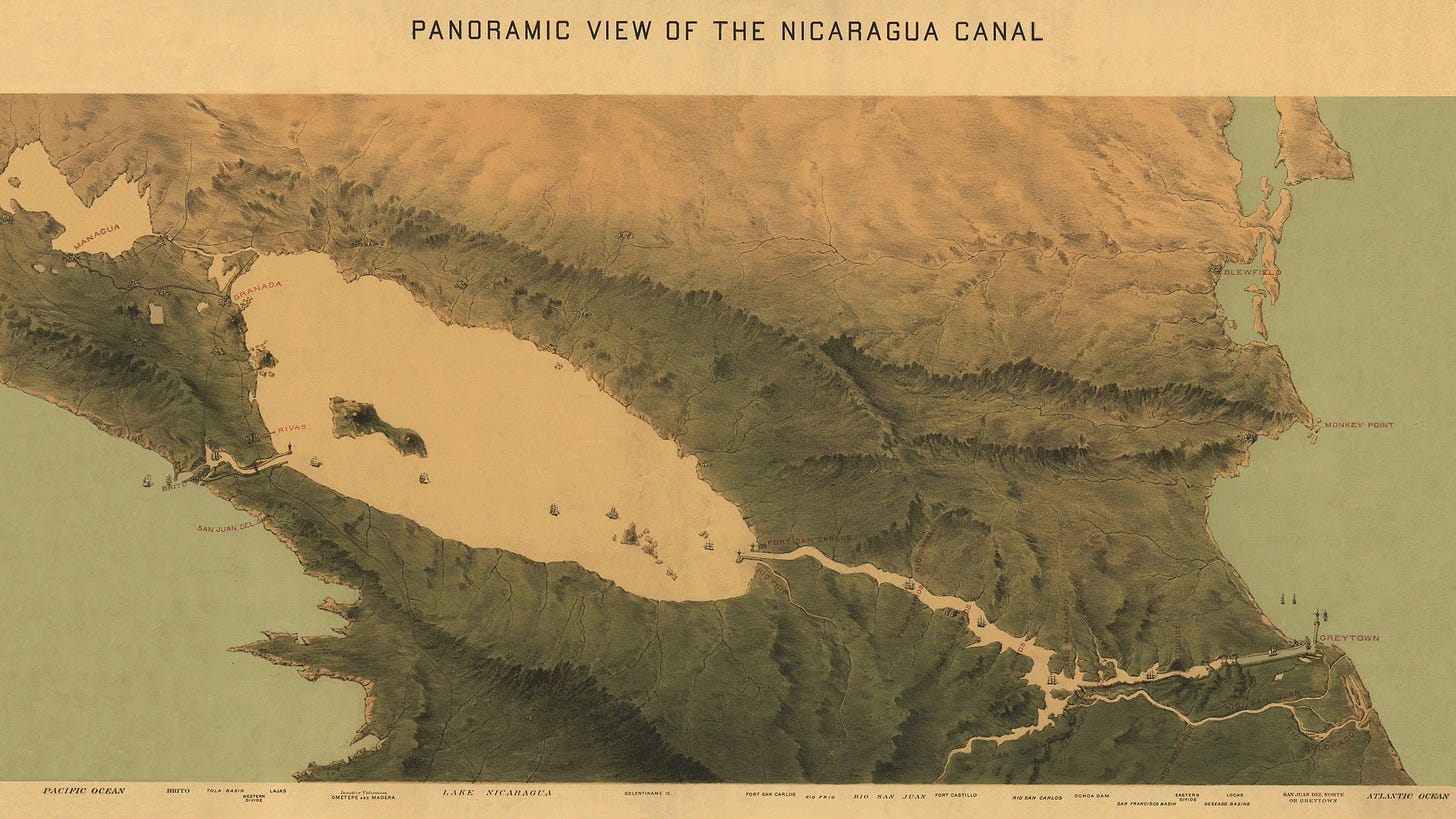

People had dreamt of digging a canal through the Central American isthmus, linking the Pacific and the Atlantic, ever since it was encountered by the first Spanish colonists in the 16th century. Doing so would save ships thousands of miles of treacherous passage through the Drake Passage and Cape Horn on the southern tip of South America. But no-one could quite agree on the best location for the crossing.

Some pointed towards the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico, others suggested a crossing in Nicaragua. Then there were two potential routes in Panama - one over the Darién Gap, a vast uninhabited jungle between modern day Panama and Colombia and another crossing from Limón Bay to Panama City.

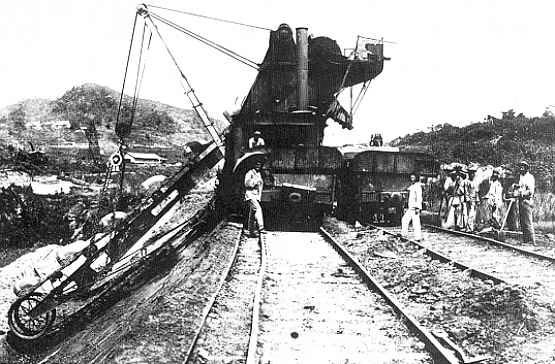

The French plumped for the latter option - for not entirely rational reasons. Having just completed work on the Suez Canal, French entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps decided he was the man to cross the Central American isthmus too. But he was determined that, as in Suez, this canal should be a sea level canal - in other words it wouldn’t have any locks to lift ships up and down.

This was a silly idea. It is silly today: Panama is far more mountainous than Suez; digging a canal at sea level would involve displacing a nearly impossible amount of rock; and while Suez doesn’t have to contend with much in the way of tides, there are enormous tidal differences between The Atlantic and Pacific. It was even sillier in the late 19th century, when the machinery wasn’t big or powerful enough to move the necessary earth to create such a canal.

So while the Frenchman pursued his silly idea, the Americans spent a long time thinking about where to build a canal and came up with a more sensible idea: build it not in Panama but in Nicaragua.

A canal there would have a few advantages. For one thing, Nicaragua is closer to America than Panama, so ships wouldn’t have to sail as far out of their way to get there. Even more compellingly, the amount of canal you’d have to dig would be considerably less, since ships could go via Lake Nicaragua. The downside was you’d have to build big locks to get them up and down from the lake, but a number of reports suggested a Nicaragua canal would be considerably cheaper and more practical than one in Panama.

However, one moral of history is: never to tell a Frenchman he’s being silly, especially someone like Ferdinand de Lesseps. Because America’s disapproval only encouraged him to double down on his plan. And between 1880 and 1889, he led a bold expedition to dig his sea level canal across Panama.

It was an utter disaster. The land was too challenging, the workers fell victim to tropical diseases. De Lesseps eventually conceded that his original plan was flawed, and that he would have to introduce some locks (in other words, that sea level canal - the whole reason he chose Panama - was a non-starter). But by then it was too late. Extraordinary amounts of money were lost - so much so that it caused a major political scandal which took down much of the French establishment.

Even after the French plan imploded, America was still set on building a Nicaragua canal. In terms of total cost, it was still the cheaper, more sensible option. But this is where we come back to Bunau-Varilla - the man who would eventually blackmail Panama into signing the Canal Zone to the Americans. He had been working as the general manager of de Lesseps’ canal company when it collapsed, and had been left with a lot of seemingly value-less stock as a result. In an effort to earn back some money, he spent years trying to persuade the Americans to complete the work the French hadn’t quite finished.

And he had a point. Once you adjusted for the work already done by the French, it was somewhat cheaper for the Americans to finish their Panama Canal than to build a brand new one from scratch in Nicaragua. So America decided the canal would be in Panama, not Nicaragua. And this is what brings me to my even more preposterous idea. Why shouldn’t the Americans go back to their original, original plan and build a canal in Nicaragua?

The Nicaragua Canal Mk III

You see, the Panama Canal has some pretty profound problems. One is that the locks aren’t big enough to fit the world’s biggest ships. Even more problematic is the fact that it is running out of water. That might seem like an odd thing to say about a canal, but this comes back to the fact that unlike Suez, a sea level canal, Panama needs locks to function. And to make canal locks work you need a lot of water in a lake or reservoir at the top - so that water can fill the locks each time a ship wants to be lifted to higher altitude.

The way this worked in Panama was that the fearsome Chagres River was dammed to create a massive artificial lake in the middle of the country - Gatun Lake. Gatun is massive, but so too are the water demands of the canal. The passage of a single ship necessitates more than 50 million gallons of water to be drained out of Gatun and into the locks. According to this article, “Every day, the canal uses two-and-a-half times the amount of water consumed by the eight million residents of New York City.”

And the challenge in Panama is, partly down to changes in rainfall patterns (possibly due to climate change), partly down to the large amount of traffic through the canal, water levels in Gatun Lake are falling. Indeed, a recent drought forced the authorities to limit the number of ships passing through the canal. This is a big deal - near existential for global trade.

All of which is why talk of a Nicaragua canal hasn’t ever gone away.

There are plenty of reasons to be sceptical about a canal through Nicaragua. For one thing, there are big environmental questions about churning through parts of the rainforest and Lake Nicaragua. But there’s also the promise of building a canal which doesn’t suffer Panama’s problems: which could carry bigger vessels and which wouldn’t face water shortages (Lake Nicaragua is far, far bigger than Gatun Lake).

Up until recently, a Chinese company had been planning to build a canal through Lake Nicaragua. That plan was cancelled last year. But Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega is still busy trying to persuade Chinese investors to build another canal across the country - albeit not via Lake Nicaragua.

On the basis of his social media posts, part of Donald Trump’s annoyance with Panama is the presence of Chinese soldiers there. Would he really be comfortable with China actually building a canal even closer to the US?

Of course, the most likely outcome is that the Nicaragua canal remains where it has done for a century and a half - a fantasy in a few peoples’ minds. A route via Lake Nicaragua - let alone the one being touted by Ortega today - would be eye-wateringly expensive. It is, as I promised, utterly, utterly preposterous.

But is it that much more preposterous than overturning a recent treaty in favour of a seriously dodgy treaty drawn up by a Frenchman more than a century ago?

Extremely interesting reading 👏👏. Would you mind answering the two comments below? One of which denigrates our future president soundly (but I suspect he will not mind, having been savaged for 4 long years by the current administration, led by a senile, bumbling fool - I am resembling him as I'm in my late70's 😉).

It’s worth mentioning that there is not one Chinese soldier at the Panama Canal, not one. That alone makes Trump’s inane bluster risible. That this article glosses over the very essence of Trump’s bombast makes it suspect.

I was at the Canal Zone for work the week before Trump’s speech. I was at the memorial for the many students the US murdered in 1964 the day after his speech. He has managed to enrage a country that has been a close ally of the US. Also, this article fails to mention the enormous expansion of the canal completed by the Panamanians in the last decade. Besides doubling its capacity, it more than tripled the allowable size of container ships it can accommodate. Servicing this debt (something the Chapter 11-loving Trump knows little about) explains the rates to use the canal, which shipping lines readily commit to paying by securing slots up to a year in advance.

Finally, this unfortunate article breezes past the many challenges of the Nicaragua scheme, not the least of which are the myriad sharp bends in the rivers. Over 120 years ago these were deemed impossible for the little ships of the day. The amount of earth that would need to move for a 26,000 TEU container ship cannot be imagined and is beyond ‘preposterous.’