The Most Important Chart in the World

Finally we're starting to put figures on how much other countries are helping their industries. Now let's start discussing what to do about it.

A few months ago I was chatting to a senior policymaker here in the UK who said: “Have you seen that chart on state aid from the OECD? It’s extraordinary.” The answer, as it happens, was no.

It took longer than I expected to track down the dataset that policymaker was referring to, buried as it was in the depths of the OECD’s online library. If you’re curious, the best place to begin is this report. Anyway, it was well worth the search. Because this chart helps answer one of the most important questions in the modern world.

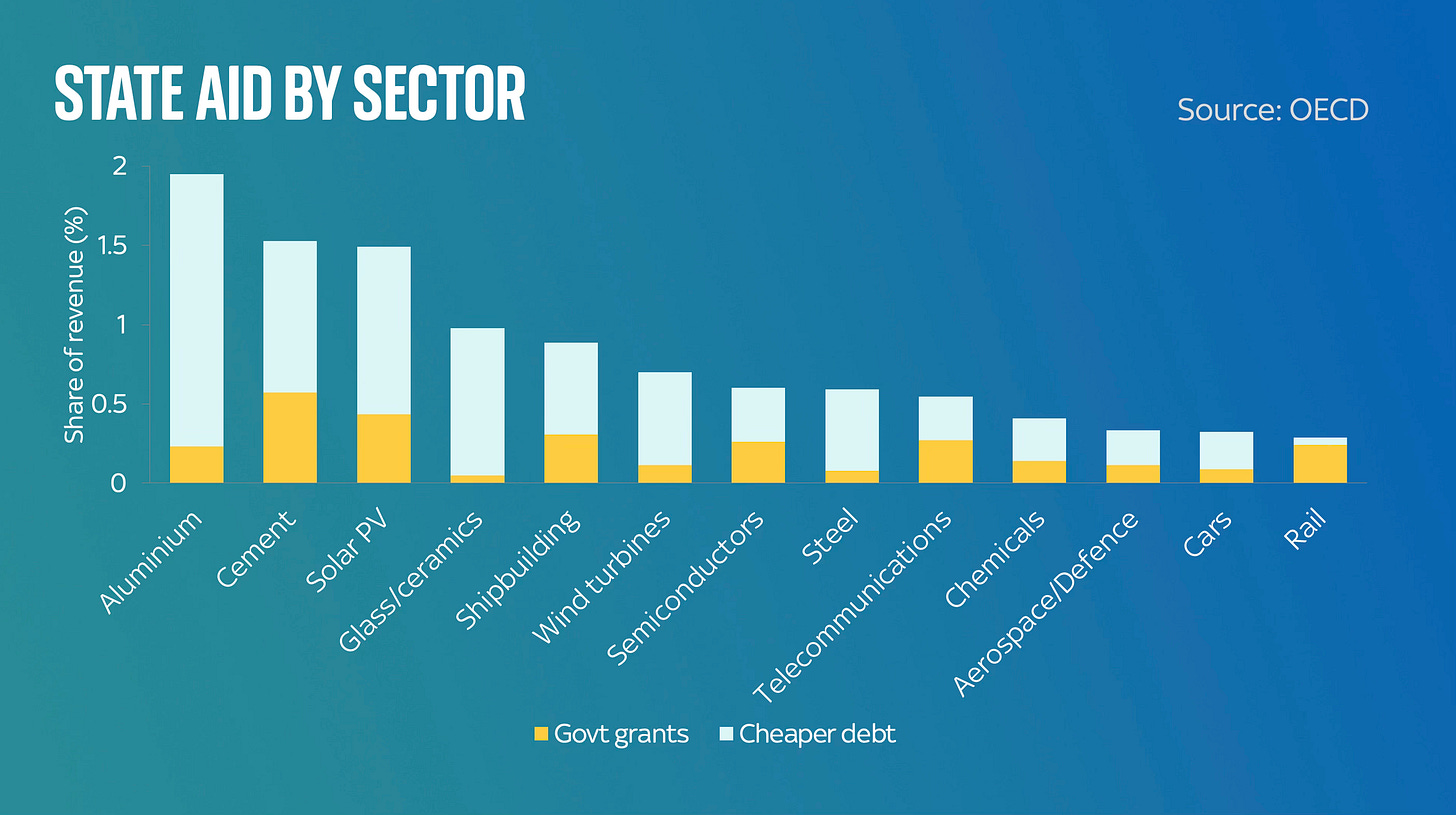

If you’re wondering how and why it is that so many parts of the UK and US have deindustrialised so fast, or why China has such a commanding lead in the production of everything from steel and concrete to solar panels and electric car batteries, then this chart provides part of the explanation.

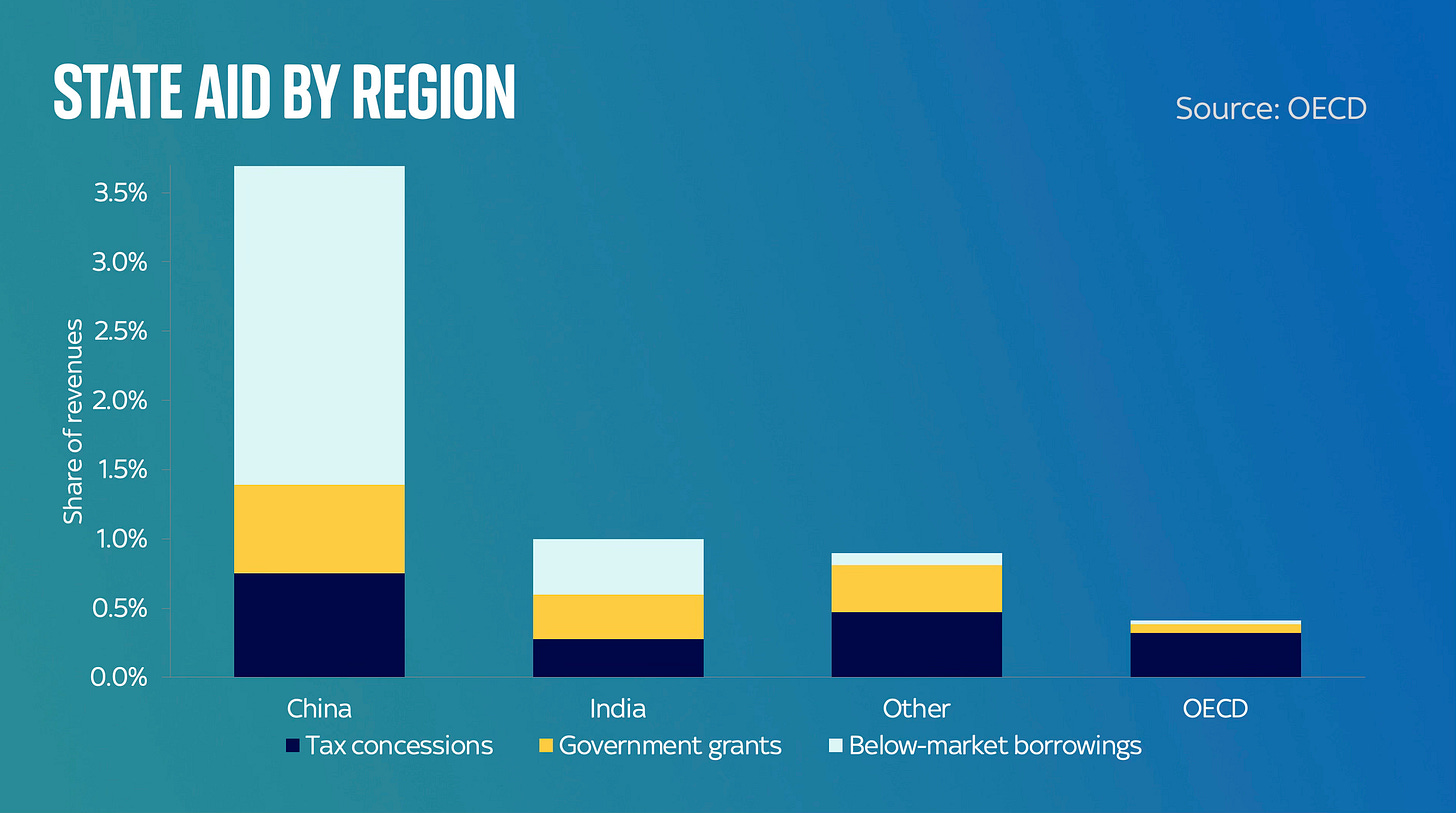

For what this chart shows you is how much help Chinese companies are given by their government - either in terms of simple grants, or tax breaks and of below-market borrowing. And what it shows is that the amount of state aid enjoyed by Chinese companies is more than nine times the amount enjoyed by companies in the OECD, which is to say the developed world average.

What’s perhaps most interesting about the analysis (and what helps explain why this kind of analysis has been so long in the coming) is that rather a lot of the Chinese lead in state aid is explained not by the traditional stuff you’d expect to call “state aid” - the subsidies and tax breaks businesses sometimes get - but another form of help: being able to borrow at below the prevailing rates of interest.

Note, however, that this is still only a partial picture. How, for instance, is one to account for the fact that, say, a Chinese battery maker is helped out enormously by the fact that the Chinese government has done everything in its power to locate lithium refining in the country? How can one account for the fact that China is happy to burn as much coal as necessary to make the chemicals and power the plants which enable the rest of these supply chains to function?

Still, this chart is a start. And happily now a few think tanks and analysts have noticed. There was a very good paper by the Kiel institute recently taking in these numbers, alongside a few other indicators on Chinese state aid.

But in another sense your initial reaction might be: well, so what? After all, everyone has known for ages that China provides generous help for their businesses. It’s a statement of the obvious, surely?

Well, yes. But the problem is that measuring this stuff - detecting this stuff is far harder than you might have thought. There is pretty good data out there on the amount of subsidy farmers and fishers tend to get, but up until now there simply hasn’t ever been a decent measure of the subsidies enjoyed by, say, wind turbine manufacturers.

The upshot is one of the biggest issues in the global trading system. Without the data to prove it, rich countries have struggled to challenge China in formal multilateral bodies like the World Trade Organisation, even though it has been patent for many years that when they make steel or aluminium or solar panels they are not completing on a level playing field.

And the upshot of that is, well, everything else. The US and UK (and a fair few other countries besides) have deindustrialised at a rapid pace. Vast sections of their industrial geography have been hollowed out. Steel mills have been closed, metals refineries shuttered, manufacturing plants closed because it is impossible to compete with China.

Now at this point it’s worth underlining that these subsidies are hardly the only thing that has allowed China to become so dominant in so many economic fields. For a long time, Chinese labour costs were considerably lower than in the US or even Mexico (though the differential is no longer so wide).

China’s dominance in some sectors like steel and concrete (and to a lesser extent copper and aluminium refining) reflects the fact that it is the final market for many of these products. Most of the steel it’s making is for its domestic market. Though the surplus is then sold elsewhere.

And also China has become very good at making certain items - stuff like batteries - though it’s not exactly evident this pre-dated the support provided by the state for certain sectors.

This brings us back to a critical point, one made recently by economist Michael Pettis. When trade economists look at why certain countries seem to dominate a particular sector or product they often point to the Ricardian idea of “comparative advantage”. We make a lot of this item because we’re just really good at it. But, says Pettis, China’s dominance in certain fields doesn’t look like comparative advantage but competitive advantage: it’s very hard for anyone to compete because the playing field isn’t level.

There are some, let’s call them “establishment economists” and commentatorswho would say: “ok but so what.” So what if China is subsidising its battery and wind turbine sectors if the result is cheaper EVs and green power for everyone. China will help us achieve net zero - hurrah!

To quote Pettis (my emphasis):

To put it differently, if China subsidizes EV exports, American consumers of EVs do indeed benefit from cheaper prices. But whether Chinese producers or American producers pay for the cost of these subsidies depends on whether higher Chinese exports result in higher Chinese imports or higher Chinese surpluses. In the former case, one set of Chinese producers pays for the subsidies delivered to another set of Chinese producers. In the latter case, it is US producers that pay for the subsidies delivered to Chinese producers.

In other words, when you take into account the cost of the industrial jobs lost in places like the US and the UK, it’s not altogether obvious that we’re getting a good deal here. It’s not altogether obvious that the conventional wisdom as espoused by the Economist and the FT and, for that matter, the Treasury in London, is right here.

All of which is to say, these numbers matter. This chart is really, really important because it is the most coherent bit of data thus far underlining that what we’re looking at here isn’t a story of China’s comparative advantage but competitive advantage.

What you’re seeing when you see steel plants closing in the UK is at least in part a story of that chart above (though, yes, with steel it’s about energy competitiveness too - and net zero policies and a fair few other things. Another blog on steel coming soon).

But there’s a bigger point here. As the book makes clear, if we are committed to net zero, then we are committed to trying to achieve another Industrial Revolution. But if there’s one country with a commanding lead in that Industrial Revolution, it’s China. And we should be asking ourselves: how did this happen? And I think part of the answer is that we became enormously complacent about the power of industrial strategy - or rather, what happens to a laissez faire nation in the face of industrial strategy elsewhere. In such cases, it’s entirely fair to argue that we should do nothing - as the Economist et al tend to. What no-one should pretend is that doing nothing is somehow a neutral choice. It’s not.

That chart above underlines it. So we need to discuss the chart, and we need more research on how much help certain countries give their countries. We need to understand, for instance, what the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act in the US would make the American equivalent of that chart look like.

Perhaps I was overdoing in calling this the most important chart in the world. But by now perhaps you agree this stuff is important, and we need more charts like this soon please.

There’s plenty of “state aid” in OECD countries… it just doesn’t go to productive people.

what amazes me is that this was pretty obvious decades ago but the lazy/greedy/incompetent western political and business leadership were too busy canabalising public infrastructure and inflated property markets to care - China has also benefitted from years of blatant patent theft, market protections and cheap labour - China has also been lending other countries money to buy things from China - at some point all of this must fall apart but in the meantime we party on.