The Most Hopeful Chart in the World

And its evil twin...

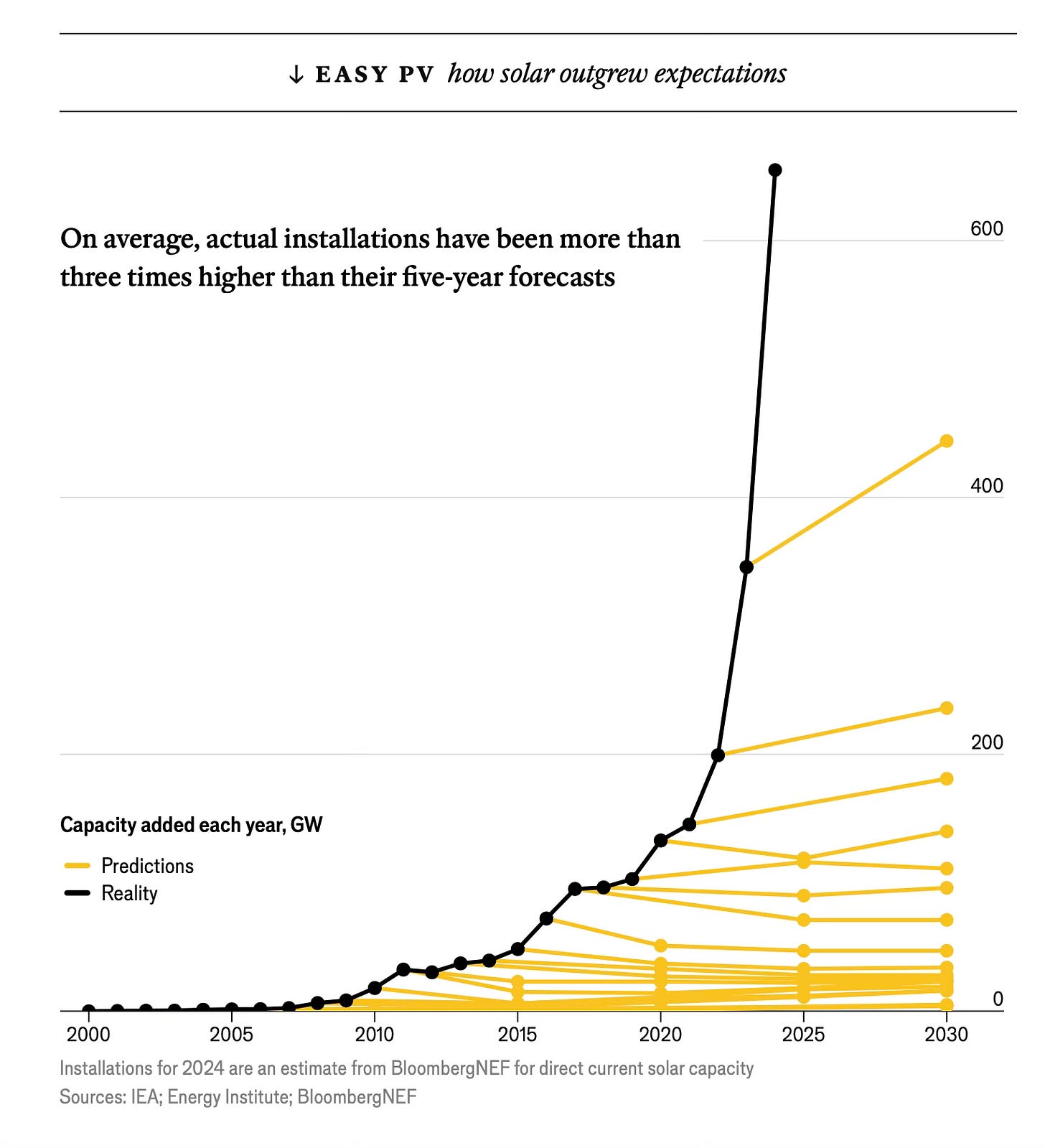

If, like me, you’re a bit of a techno-optimist, and you hope or suspect that technology will help provide at least some of the solutions to the various quandaries we’re facing right now, you’re probably familiar with this chart.

The version I’ve borrowed above comes from this excellent Economist piece about solar power but it was originally made by Auke Hoekstra, and has been reproduced many times since. Here’s one from the folks at Carbon Brief.

Anyway, what the chart shows is powerful: year after year the International Energy Agency (generally seen as the global authority on this stuff) predicts that the amount of solar capacity around the world will soon plateau, or will only rise very gradually. But year after year something very different happens: the amount of solar out there has risen exponentially.

Hurrah! And if you put this chart alongside the other promising charts showing, for instance, that the price of solar panels is also going down rapidly, so much so that they are cheap enough these days that the Dutch are using them as fences, you might be left with the impression that technology has already ridden to the rescue here. In fact, you might be wondering, why on earth is anyone panicking any more about the energy transition?

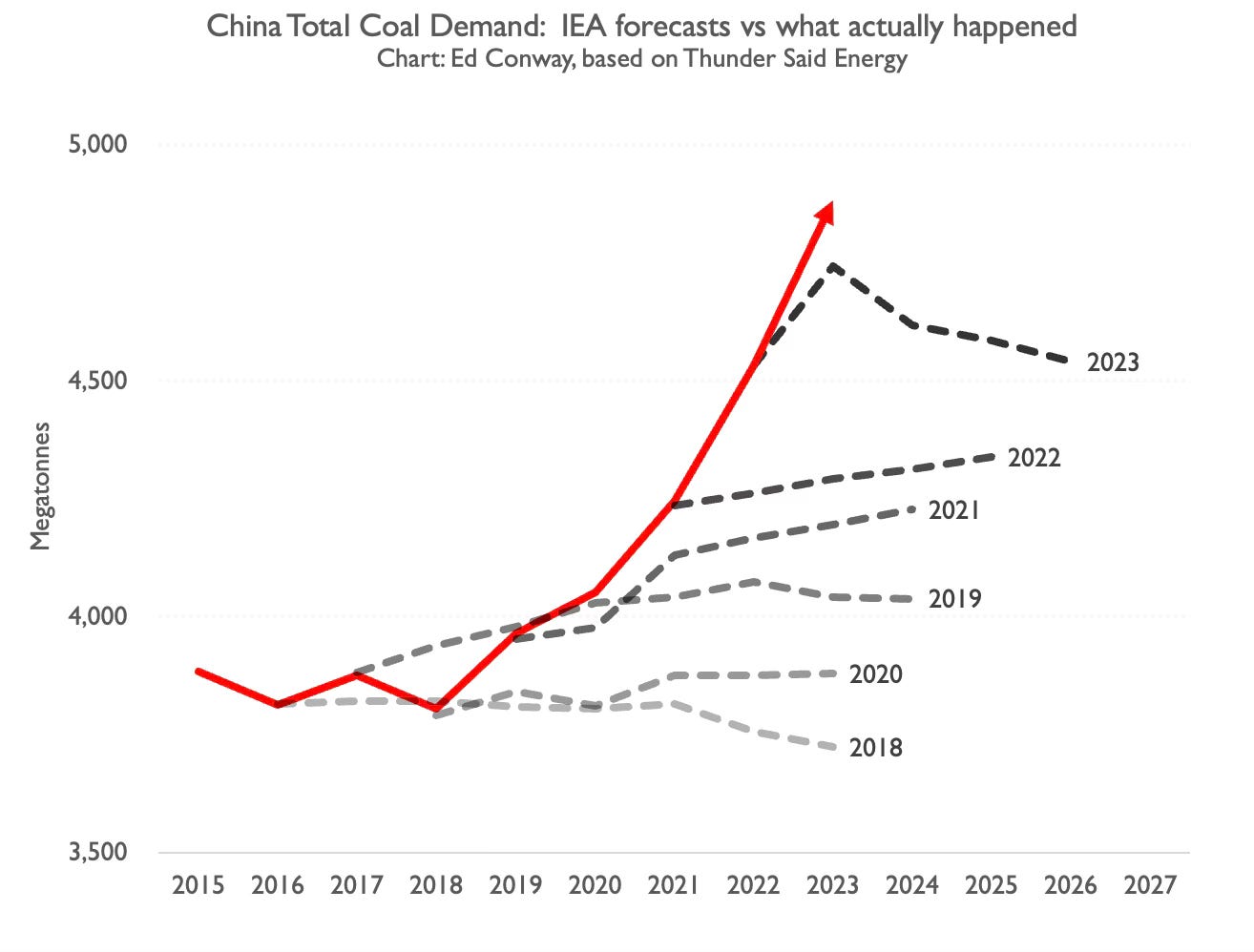

But here’s the thing. This chart has what you might call an “evil twin”, a cousin that gets far less of an airing - but probably should. In fact, the only place I’ve seen it is in a newsletter from the excellent Rob West. Here’s what it looks like:

You can see it’s broadly speaking the same pattern. But this time we’re looking not at total solar output but something else: the total amount of coal being burned in China. Every year the IEA predicts that coal consumption will plateau or drop. And each year it turns out to be wrong. In fact, China burns ever more coal.

This is a big deal, a really big deal - and yet it’s often glossed over by policymakers. Since every year the IEA can predict that coal output will soon peak, politicians can continue to claim that the transition is happening - that coal is being consigned to history. Yet while some countries, most notably the UK, are ending their reliance on coal for power, those changes are little more than a rounding error in the face of the global picture - that coal is still powering much of the world.

I mention all of this because yesterday the IEA came out and admitted what has long been apparent to anyone paying close enough attention: that contrary to its recent claims, coal is not peaking. Indeed, for the first time in many years, it produced a forecast for global coal consumption that sees it rising slightly rather than falling slightly in the coming years (look at the 2024 line for China below). We are, in short, some way away from peak coal. This is a big shift.

But the broader point that’s worth pondering is the extent to which the two charts - solar and coal - are linked. Because most of those solar panels and electric car batteries we’re buying in Europe are ultimately dependent on Chinese coal.

As you’ll know if you’ve read Material World, making a solar panel (or silicon chip) involves the use of metallurgical coal. Making a car battery is an energy intensive process. And while it’s certainly the case that many Chinese plants are using ever more renewable power (and there’s a virtuous circle: more solar production means more panels which can power some of that production) for the time being most Chinese industry is still powered by coal. Albeit that they’re covering all industry - not just the green stuff, those aggregate coal consumption figures tell a stark story. As Javier Blas puts it, the green transition is powered by coal.

Our politicians might not like to discuss this. But in Europe in particular, the transition depends rather heavily on buying cheap Chinese technology to enable us to meet all those mandates for green vehicles and power. We probably couldn’t afford it otherwise. And that also means depending on Chinese coal. What else did you think was powering most of those factories?

True: a good proportion of the fall in Chinese green product prices (think: those solar panels so cheap you can turn them into fencing) is due to learning curves and enormous scale of production in China, at least some of it comes down to the fact that coal is still the cheapest form of firm (that is to say, 100 per cent available 24 hours of the day) power.

It’s all intertwined.

None of the above should stop any of us from being techno-optimists. It’s still possible to envisage a future with lower carbon emissions. That chart at the top is still incredibly inspiring. But it also has a dark side, about which we shouldn’t delude ourselves.

The more we in Europe come to expect ever cheaper Chinese batteries and solar panels (while ignoring the hidden story of how these products are actually made), the more coal will be burned in Chinese power stations and metallurgical silicon plants to give us those cheap items.

The charts are two sides of the same coin.

I'm sorry, Ed, but I find your first chart just plain depressing. Its prominence is yet more evidence of the utter lack of systems thinking among so many today. There is zero utility in exponential expansion of an energy source that is often unavailable and is use-it-somehow when it is on, without cost-effective ways to make it part of a 24/7 energy system.

And that is even without contemplating the folly of trying to move humanity to energy sources having low energy density.

I AM optimistic about technology. Not so much about judgement.

You are right to point out that IEA have been predicting peak coal for a while and it hasn't happened. However I am very surprised that you are comparing the solar chart that starts at zero with a coal chart with a false zero to show to imply the growth rates are comparable. Not what I expect from your usually balanced analysis. Coal has only grown by 1% in the last year hasn't it? and the pace of growth has slowed considerably from previous years. Still growing, yes, but hardly comparable with the growth rates of solar.