The Glass Famine

Spies, war, industrial subterfuge and secret recipes. And it all really happened. Honestly, what more could you ask for?

When I began writing Material World I tried my hardest not to spend too much time thinking about the newsworthiness or otherwise of the content. This is not, shall we say, especially easy for a journalist. But the whole point of the book is that it needs to stand the test of time; to be readable in a decade as well as today. Let me know whether you think it passed that test.

But the upshot of all that is that I do wonder whether some of the lessons from the stories are a little subtle.

With that in mind, here is the story of the “glass famine”, one of the earliest tales in Chapter 1, in a slightly more “unsubtle” format. Hopefully for those of you who haven’t read the book it’ll give you a sense of some of the stuff I cover in there and for those of you who have it’ll drum in the relevance for modern policy.

Before I begin, it’s worth emphasising that the below is only a very brief rendition of an issue and set of events covered in much more depth in the book, which is available in most territories (save for North America) at the time of writing. Please buy it!

August, 1915

War is raging on the Western Front. Thousands are dying every day. It’s already shaping up to be the bloodiest war in history. Guns, bombs, even chemical weapons like chlorine and mustard gas.

Amid the fighting, a spy is despatched from the Ministry of Munitions in London to Switzerland, there on a very special mission. He is there to procure one of the world’s most advanced pieces of military technology.

That technology is… glass. Or, to be more precise, optical glass: binoculars, telescopes, sniperscopes.

Now while these things may sound somewhat trivial today, in 1914 advanced lenses were a massive deal. This was the first great war fought at long distances. Advances in ballistics & weaponry meant ranges went up to 40,000 to 60,000 yards. And those with the best lenses had the best chance of hitting their targets. They had an enormous advantage.

And as WWI began, there was no doubting who had the upper hand: Germany.

Germany totally dominated world production of precision optics via its company Zeiss (making lenses) and Schott (making the glass going into those lenses).

Britain, on the other hand, was reliant on Germany for around two thirds of its optics. So when the war began and those supplies were suddenly shut off, the UK was left facing a “glass famine”.

In the opening months of the war, British troops were killed in terrifying numbers by German snipers (with Zeiss scopes). British soldiers, meanwhile, were being sent out to the trenches without any binoculars. It fast became an emergency.

There was a public appeal and newspaper campaigns encouraging people to donate their binoculars, opera glasses, anything, to troops heading to the front. Even the King & Queen donated some of theirs. But it wasn’t enough.

Which brings us back to the spy sent to Switzerland. His mission was to find a way of buying binoculars off the Germans; to buy a technology off the enemy to use to kill the enemy.

This, by the way, is not supposition. It comes from the official govt account. Here’s one bit I quote in the book:

Preliminary investigations had led to the conclusion that the only country which could supply optical instruments in bulk was Germany, and in order to obviate a breakdown in the supply of these essential instruments a representative of the Ministry of Munitions was sent out to Switzerland in August, 1915, to ascertain whether it was possible to obtain instruments from German sources.

The only thing crazier than this proposal… was that the Germans actually said yes. They were not just willing but seemed to bend over backwards to provide binoculars (to be used to help kill their troops). Here’s the passage from the history of the Ministry of Munitions:

Why were they willing to provide this advanced military technology to their deadly enemy? Because in much the same way as the UK was desperately short of glass lenses, Germany was desperately short of rubber for their tyres and engine fan belts. And the UK controlled much of the global supply of rubber via her colonies.

So, for a period the two great powers were so desperate for raw materials they were willing to suspend the normal conventions of warfare. Rubber for glass.

How did we get here?

Before we go further (because what happened next is poss even more interesting and has some practical lessons for today), it's worth delving into why Britain found itself so short of glass in 1914.

Because as it happens, a century or so earlier it had a world-leading optical industry. And glass - humdrum as it might seem - was the great advanced technology of its day - a little like semiconductors are today. I covered this a bit in a previous post. Glass lenses gave people bionic powers; they increased the size of the working population; they enabled scientific research. They probably help explain the Renaissance, for heaven’s sake!

Making glass (melting sand!) was not easy. But in the 17th and 18th centuries the UK had one of the most advanced optical research sectors in the world. Everyone was carrying out research into glass.

And British lenses were, by most accounts, far better, clearer and more precise than their Bohemian counterparts. The glass sector became one of the most profitable and important in the UK economy. Foreign powers routinely sent spies to try to plunder its secrets. So what went wrong?

The picture above is a clue. In the 18th and then 19th century there was a sequence of taxes on glass. Most famous of all is the window tax of the 18th century which, in fairness, wasn’t primarily a tax on glass. It was mostly a tax on housing (the more windows, the more you paid - hence why people bricked in windows).

But it was the beginning of a fiscal assault on the glass sector. The crystal goose was to be plucked. The window tax was followed up by further taxes on glass producers and on glass consumers. There were duties and other charges, many of them based on the weight of glass.

And the consequence was that the sector retrenched. Businesses failed to invest in new types of glass. Domestic glass became too expensive.

The irony is that this was happening just as the biggest breakthroughs were happening in glass. Scientists were devising recipes for more resilient glass; clearer glass; glass for ultra powerful lenses, microscopes, binoculars.

But the industry wasn’t interested. Not enough money to invest in actual production. The companies (and there were a fair few in the UK) focused instead on improving the cost effectiveness of their existing product lines. Corporate R&D, such as it was, went out of the window.

Even at this point, policymakers in Germany were doing quite the opposite, providing support and tax breaks for their glassmakers (and other scientists). With the help of what would today be called “industrial strategy”, Jena in Thuringia was picked as a centre for technical glassmaking. An enterprising scientist, Otto Schott, came up with clever new glass mixes, including borosilicate glass and clever glasses which used lithium to become clearer and more stable.

Carl Zeiss then turned Schott’s glass into amazing lenses. An industrial sector was born; Jena quickly came to dominate lensmaking. Part of that was down to the genius of these men but partly it came down to the economic environment which was supportive even as the environment in the UK was not.

Gradually, UK production of lenses fell. The British did what they always do: bought the product from wherever would sell it to them cheapest. And laissez faire government policy encouraged this. Which brings us back to 1914, by which point the UK relied on Jena lenses for 60% of its binoculars and other optical glass.

And so we ended up where we ended up in 1915, with the British so short of binoculars they offered to do a secret deal with the enemy. With officers from both sides staring at each other through identical binoculars. Here's a passage from an officer's account of the battle of Jutland:

But as I say, the most interesting thing wasn't so much that deal, but what happened next. The official account says despite the Germans saying yes, the British never took them up on the offer. Some historians have argued the lenses were delivered. But let’s look at the data…

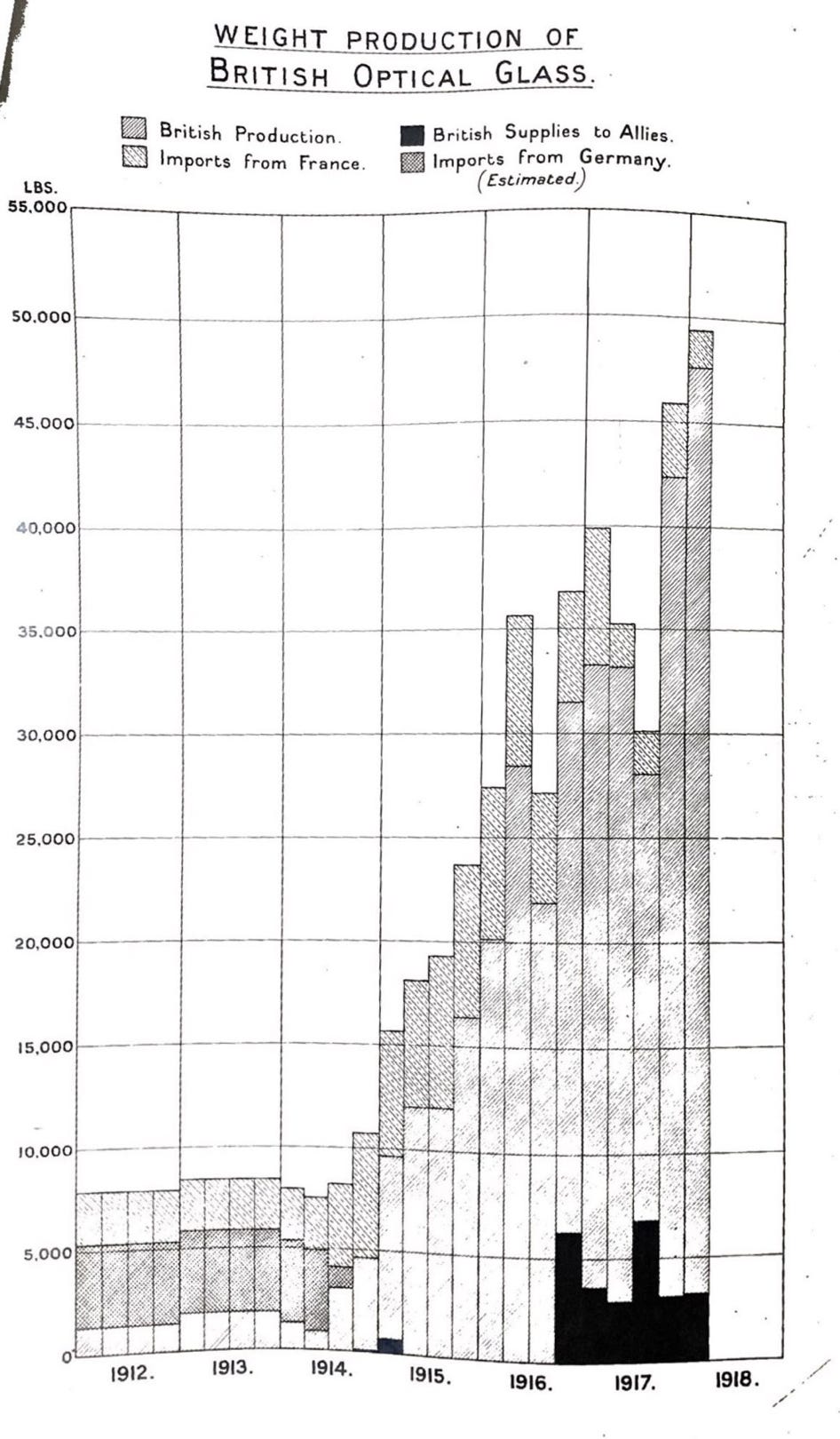

Here’s a chart I dug out of the UK National Archives while researching Material World. It shows you optical glass supplies to the UK. And look: the standout thing is how quickly UK domestic production rose.

The UK didn’t need German glass by the time that deal was done because it was producing plenty by then, and output was rising fast. UK factories had swung into action. They turned around the deficit so quickly that by the end of the war they were producing more than they needed - enough to supply their allies.

The glass famine, in other words, was followed by the glass feast.

(the other thing to note is what happened AFTER this chart: having rebuilt its glass industry, the UK allowed it to waste away again. By the post-WWII period it was back in the doldrums. Most of the optical producers shut down. It was a short-lived feast).

So what are those unsubtle lessons for today?

The first is that our dependence on certain countries for key products is not trivial. Or at least, it seems trivial until suddenly it isn't. UK didn't think twice about where binoculars came from til 1914. It just bought the cheapest stuff…

And as you can see from the chart below, that's precisely what we do today with batteries, solar panels, rare earths, with many other critical ingredients. We buy them from China. For some we are more reliant today than the UK was on Germany in 1914.

All of which is fine until, well, it isn't. Until a bullet changes the course of history in 1914, and suddenly a reliable supplier of a key wartime product becomes your enemy - and you have to consider doing a deal to keep up your supplies.

The second lesson is more hopeful. It's that it is possible to resuscitate dormant or shrinking sectors. It is possible to re-industrialise quickly. Remember that old bar chart from the National Archives: within a few years UK glass production was completely turned around.

Remember this today. It can be done.

The third lesson is that decisions taken a long time ago can come back to haunt you. It was partly thanks to a suite of taxes, beginning with the window tax, that the centre of gravity for technical glassmaking switched from the UK to Germany in the late 19th century. Companies like Zeiss and Schott rose to greatness.

Roll on to 2023 and which company is it which provides the lenses at the centre of the machines making all the world's most advanced silicon chips? Zeiss.

That same company whose binoculars were so prized that WWI Britain sent a spy to do a deal with its enemy…

As I write once or twice in the book, so it goes in the Material World.

Another great read. Thank you for explaining things in ways that feel relevant and just make sense. Loved your book