Phosphogeddon Never

Why the "world-changing" discovery of phosphates in Norway isn't quite as world-changing as you might have been led to believe. But don't panic: we're not going to run out of this critical rock

If you’ve heard of phosphates before, there’s a chance you’ll have heard about them via articles like this or this. Every so often a newspaper runs a story screaming that we’re about to run out of this important category of minerals.

That would clearly be a Bad Thing. Because without phosphorous we are all dead. This element is essential to life. Without it our cells cannot grow, which would be the end of everything as we know it on this planet.

Alongside nitrogen and potassium, phosphorus is the backbone of plant life. This stuff, which we mostly get by mining it from rocks in the ground, is an essential fertiliser, part of the holy trinity of nutrients which crop up (no pun intended) repeatedly throughout Material World.

The fact that these days we also use a small but increasing fraction of the world’s mined phosphorus inside electric car batteries adds an extra piquancy to these stories. This element is a big deal, and getting bigger.

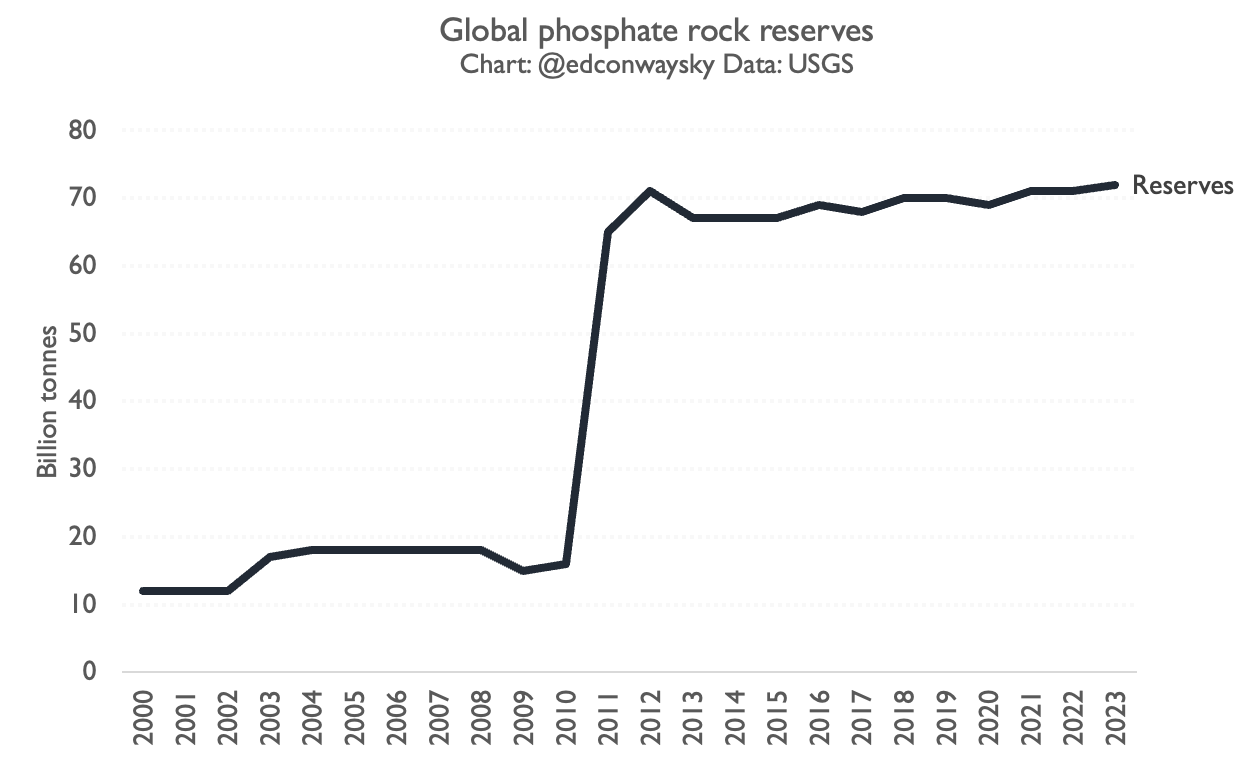

So yes, phosphogeddon, or “peak phosphorus” as it’s sometimes called, is indeed a very scary prospect. And many of those scary stories derive from simple calculations that look at how much phosphorous we’ve classified as reserves, comparing that with annual consumption and then working out how many years we have left of the stuff. Here’s what that chart looked like back in 2009: only another couple of decades until we’d hit the peak. Argh!

All of which perhaps helps explain the excitement over the recent discovery of large amounts of phosphates under the ground in Norway. The quantities of phosphates found by Norge Mining are so great, trumpeted some of the stories, that they had effectively doubled the global stocks of phosphates overnight. Amazing, right??

Except that there are a few problems here. Most glaringly, while this discovery is of course encouraging and exciting, actually it turns out the numbers are significantly less exciting and world-changing than they look on the surface. In fact, nearly all of the news organisations covering the discovery have fallen foul of a common but I’m afraid quite bone-headed statistical mistake.

Reserves vs Resources

The thing to note here is that geologists have two ways of categorising what they’ve found in the ground. The main one you mostly hear about is “reserves”. This is a calculation of the amount of metal or mineral these miners have discovered and (the important bit) reckon they can afford to extract. Usually this is the stuff they’re in the process of mining. In the case of phosphate rock, the US Geological Survey, the most reliable arbiter of this stuff, that amounts to 72 billion tonnes. It breaks down country-by-country as follows:

You can see why everyone is so excited. The number being bandied around about the phosphates in Norway is 70 billion tonnes. Plug that into the spreadsheet and all of a sudden, Norway overtakes Morocco in the chart above to become comfortably the world’s biggest source of this stuff.

Wow. And that would be reassuring from another perspective: the control of these crucial rocks would shift from a country with a questionable human rights and stability record (and also NB some of its phosphates are in the disputed territory of Western Sahara) to one of the world’s most stable/boring democracies. Double hurrah!

But here’s where reality intrudes. For reserves are only one prism through which to look at what’s under the ground. Equally important are “resources”. This is a far bigger number, including not just the stuff you know you could afford to extract and have lined up to do so, but the stuff you know is in the ground but might be a bit too expensive to extract right now.

You see the distinction. Reserves are, in mining terms at least, pretty much ready to go. They’re pretty real. Resources are a lot more speculative. There are loads more resources in the ground than reserves. When it comes to phosphates, for instance, the resources in the ground are about 300 billion tonnes, more than four times the reserves. Again, most of them are in north Africa.

And here’s the critical thing: the Norwegian phosphates are most certainly not reserves. They’re resources. They’re the speculative stuff. They’re not ready to go - not in the slightest. They may not even be economical, ever.

I’m not saying this to pooh-pooh all the recent coverage. But we need to be accurate about this. The global stock of phosphate reserves - the available stuff we know we can afford to extract without sending prices into the stratosphere - did not just double. It has not changed at all.

The global stock of phosphate resources has increased (or could do provided the USGS ends up including these numbers in their stocks). Not a doubling, but potentially a sizeable increase. It could lift total global resources by a fifth or even close to a quarter (I say could because that 300bn tonne USGS resource number was always a starting point - they say “more than 300bn” - so it’s possible the Norwegian discovery doesn’t change this number at all).

None of this is to say this discovery isn’t exciting, or for that matter a big deal. It is potentially both. Especially since these are the first major European domestic phosphate resources and given Europe (including the UK) rely on imports of this rock from overseas, this could in the long run help with resilience.

Moreover, it underlines something quite important. For all the stories about phosphogeddon (and for that matter about peak oil and copper and other resources) we humans are pretty good at finding new stuff and, even more importantly, as the years go by we get better and better at eking more minerals out of what was hitherto considered junk rock. Reserves (another important misconception) are not fixed. These amounts of stone are not set in stone. The more people panic about shortages (and the higher prices go as a result) the greater the incentive to find more stuff.

This is one of the prevailing lessons of Material World. And it’s a good news story! While the earth is by its very nature finite, it’s actually a lot bigger and deeper and more mineral rich than you might have thought. So even though our appetite for minerals is prodigious, we are also very unlikely to run out of stuff. The doomsayers almost always get it wrong on this.

The dark side of this good news story, however, is that our footprint on the earth keeps getting bigger. We need to get better at recycling stuff - especially minerals like phosphates which can cause damage to the environment if they get into the wrong places.

However, the conclusion is that while this phosphate discovery is good news - a reminder that we are really unlikely ever to face phosphogeddon - it’s considerably less world-changing than the recent flurry of press might have led you to think.

That’s doubly so when you look at some of the small print. The grades of phosphates in the Norwegian mine, for instance, look to be quite low (single figures percentages) compared with those in Morocco which can be close to 30%. It’s deep underground while Moroccan deposits are mostly on the surface. It’s early days and we’ll need more data from these exploration sites, but there are big question marks about whether these rocks will ever be classified as reserves (eg economically extractable).

Phosphogeddon and Data

Still, it’s worth noting that it’s not only newspapers who sometimes turn resources into reserves with the flick of a pen. To see what I mean, have a look at the following chart of phosphate reserves from the USGS going back the last few decades. Can you spot anything?

Look at the jump in 2011. What happened? Was there a sudden discovery akin to this Norwegian one?

No: something much more prosaic. The International Fertilizer Development Center published a report in 2010 changing its methodology on how to count the Moroccan phosphates. All of a sudden it recategorised loads of the Moroccan resources (the uneconomical stuff) as reserves.

Now, one argument is that this made lots of sense: those resources were actually far richer and cheaper to extract than previously assumed. But some argue that the flip was slightly suspect. They think the IFDC might have made a similar mistake of mistaking resources for reserves, with the upshot that all of a sudden the world went from looking like it was sleepwalking towards phosphogeddon to, well, being a lot more relaxed. All because of a statistical change. Hmm.

It’s a reminder that it pays to look at the small print about these discoveries. And perhaps a reason not to be too blithely relaxed about our supplies of this mineral.

Still, the news is mostly good. We are getting better at finding important minerals. We are getting better at getting them out of the ground. We probably won’t need to mine on the moon or under the ocean (though, while we’re at it, there’s even more phosphorous in rocks under the sea, and, who knows: this stuff might end up being just as cheap to mine as the stuff under Norway). Each year we mine crazy amounts of stuff and far from falling, the available reserves usually go up rather than down.

It is all just another reminder that we are living in a Material World.

An excellent article but one that fails to mention that cadmium contamination is a major issue with many of these resources and reserves that renders them unusable.

NZ has a cadmium contamination issue across much of its arable land from using Nauru phosphate that contains cadmium at levels several hundred times the acceptable limit for human exposure through the food chain - that is why NZ is now using contentious Moroccan phosphate because it is one of the few sources of cadmium free phosphate rock. Cadmium is a particularly nasty poison that impacts on human health at very low concentrations- much worse than arsenic.

So the peak in "useable" phosphate actually is likely to be much closer than this article indicates. Think about this next time you flush the toilet and send your daily intake of nonrenewable phosphate down the sewer and out to the ocean. Disposing of our human excrement into our rivers and oceans is only a recent phenomenon - up until the 19th century it was highly valued as a fertiliser.

Without phosphate NZ doesn't have an agricultural economy and without an agricultural economy we dont have an urban economy as agriculture pays for nearly all of our imports.

Just checking. Should that million be billion in the 11th paragraph?