No, Elon Musk is not our Henry Ford

The 21st Century's Henry Ford is someone you've probably never heard of. And that raises some other, even more interesting, issues...

Not all that long ago it was quite fashionable to opine that Elon Musk was the new Henry Ford. This wasn’t, by the way, a statement about either car magnate’s political or personal views, though these days that particular comparison is a little more prevalent. No, the idea was that in the 21st century Elon Musk would do for electric vehicles what Henry Ford did for motor cars in the 20th century.

It’s hard to overstate just how important the Ford Model T was for the adoption of the motor vehicle. It pretty much single-handedly turned cars from a luxury item into something nearly anyone could afford.

Cars - petrol, electric and steam-powered - had been around for many years before the Model T’s debut in 1908, but they remained pretty rare. While it’s sometimes forgotten today, cars took longer to become a dominant mode of transport than, say, it took for railways to beat horse-drawn carts. And part of the reason for that was that cars cost a lot.

To put this into perspective, the first production car made in the US, the Duryea Motor Wagon, cost around $1,500 at the turn of the century, equivalent to more than $50,000 today. The market for such a car was small - in the thousands. But then along came Ford, who wanted to “build a motor car for the great multitude… it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one.”

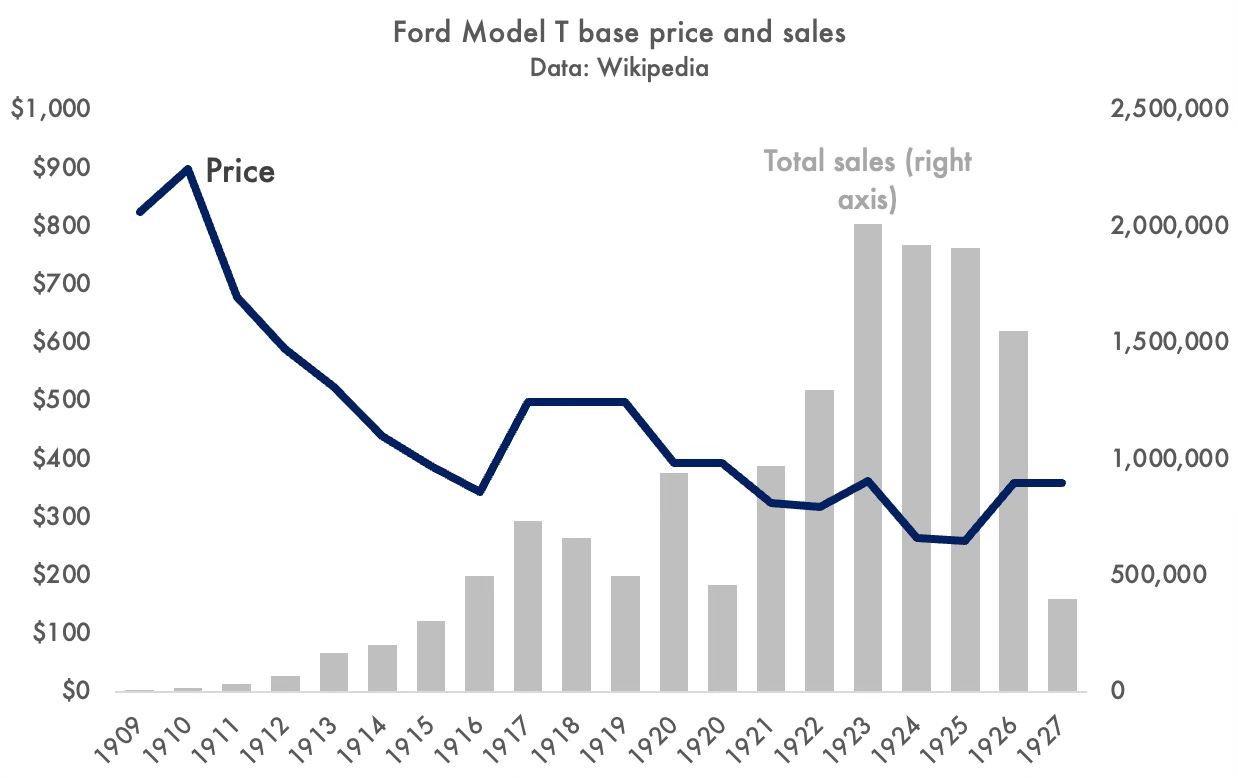

True to his word, he produced the Model T, which initially cost $825 (around $24,000 today). That isn’t just low by modern standards; it’s roughly the same price as a compact sedan costs today. It’s rather remarkable to reflect that the average car costs the same today (in real, inflation-adjusted terms) as in 1910. But then that’s the legacy of Henry Ford.

Indeed, the price of the Model T only went down thereafter. As Ford mastered mass production and reduced the cost of manufacture, the price of each year’s Model T fell rapidly. By the mid-1920s it was going for $260 - barely more than $5,000 in today’s money.

It was thanks in part to these cheap prices (and, in fairness, a few other advances including the invention of the starter motor) that petrol cars became commonplace. Something which previously sold in the thousands began to sell in the millions. In the process, Henry Ford effectively hammered the final nail into the coffin of the nascent electric car industry (though, as you’ll know if you’ve read chapter 16 of the book, the main reason electric cars took so long to become mainstream was because it took nearly a century to invent a good enough battery).

Up until quite recently the prevailing assumption - encouraged by statements from the man himself - was that, having launched his electric car company, Tesla, with a series of high-end models - the Roadster, Model S and Model X - Elon Musk would gradually work his way down towards a genuinely mass-market vehicle with a selling point close to that of the original Ford Model T, around $25,000. At last, electric cars would become so cheap they would be adopted by more or less everyone. Elon Musk would finally manifest as the modern-day Henry Ford who permanently changed the world.

Except that hasn’t happened. The Model 3, once touted as being that mass market model, isn’t quite at Model T levels: the base price in the US is $35,000, and most variants are considerably more expensive still. And this week Reuters reported that Tesla was ditching its plans for an even more affordable model worth around $25,000. Tesla’s Model T simply wasn’t going to happen.

Following that story, Musk posted one of those not-quite-denying-it denials: “Reuters is lying (again)”. So we’ll see what happens next.

But in a sense what Tesla does next is beside the point because it’s already clear that Elon Musk isn’t going to be the Henry Ford of the electric car. China is.

Or, if you really want to put this down to a single person, it’s maybe Wang Chuanfu (founder of BYD) or Robin Zeng (founder of CATL) or, if you want to cut out the middleman, you might say it’s Xi Jinping himself.

Because while the Tesla Model 3 is moderately cheap, it is way, way more expensive than many of the models being produced by Chinese companies right now. There’s the BYD Dolphin, a variant of which sells for $13,865 or the BYD Seagull, which you can buy in China for $9,700. These cars are not just cheap; they are cheaper than many petrol cars.

Now, once these cars have made their way across to the US or the UK they are typically considerably more expensive than their price in China (the rule of thumb is twice the price). But they are still typically a fifth cheaper than anyone else’s.

And it’s only just beginning. Just the other day smartphone manufacturer(!) Xiaomi announced plans to produce its own car, costing only $30,000 and decked with features you’d normally only expect on a top of the range model.

Now, it’s quite likely a fair few of the Chinese companies making electric cars may not survive (then again it’s probable that a fair few American EV makers won’t either). But the key point here is twofold: 1) China is producing electric cars and - we’ll get to this in a moment - batteries far cheaper than anyone else and 2) as a result it is becoming utterly dominant in mass-market electric carmaking.

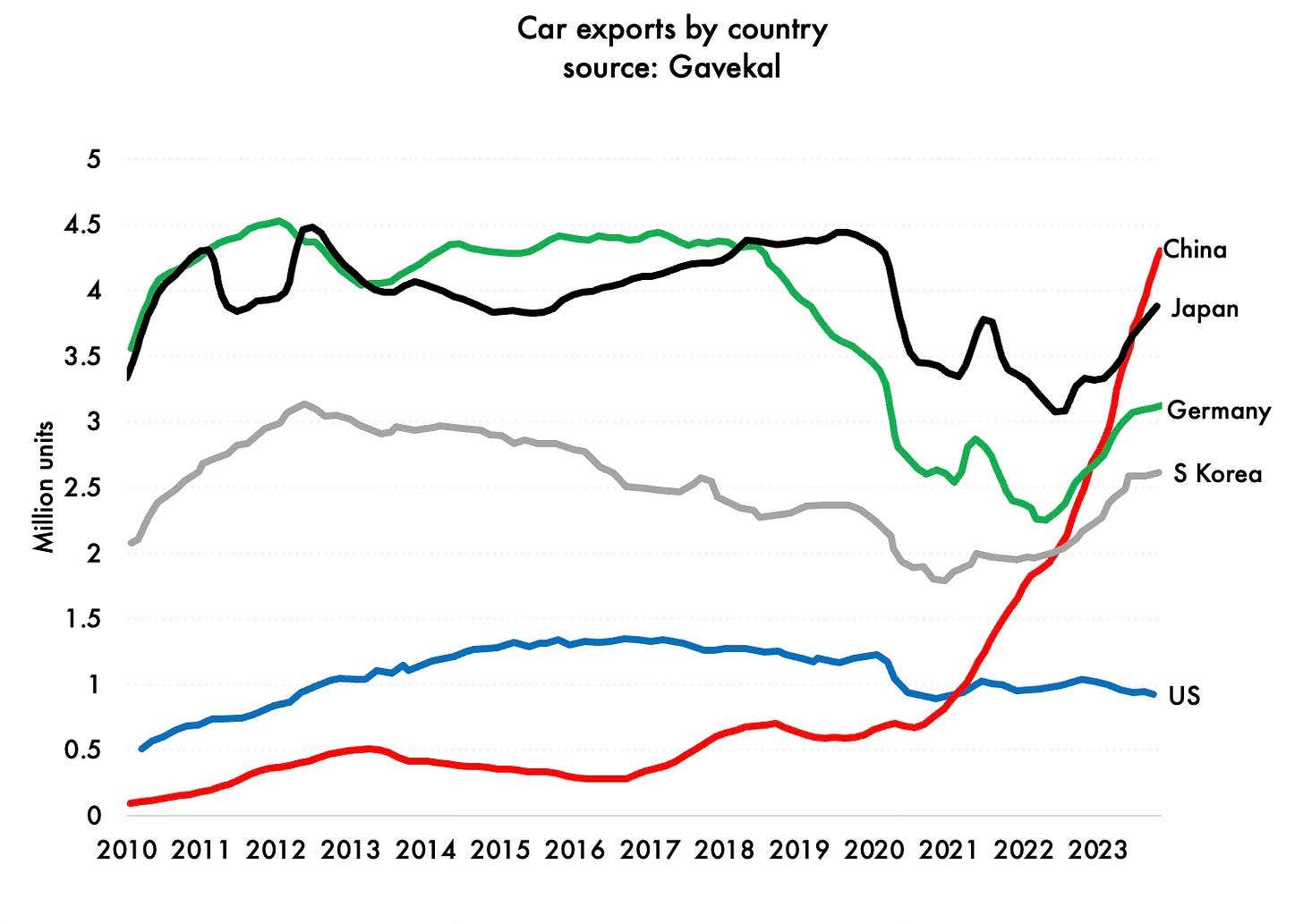

To get a sense of this, you need only look at charts of Chinese car exports, like the one above. It speaks for itself really. China has gone from being a relative nonentity in car manufacture to, well, the single biggest exporter in the world. And given the car is the iconic bit of machinery, the bedrock for the manufacturing sectors in Europe and the US, this is, well, a massive, massive deal.

How did this happen? A big part of the reason comes back to something I wrote about in Material World: China has become dominant not just in the production of EVs but - even more importantly - in the batteries that go into them. And the chemicals that go into those batteries. And the sourcing of the raw materials which are turned into those chemicals. We’re talking here about dominance all the way down the supply chain. Here’s a little bit from page 407 of the book:

This dominance may not be especially obvious on the surface, given many of the cars powered by Chinese batteries still carry American or European badges, but the deeper you delve under the surface the harder it is to escape. For not only do Chinese companies control about 80 per cent of battery production, they also control about 80 per cent of the manufacture of the materials that go into these batteries.

It’s very hard (arguably impossible) for an American or European company to make an EV without some parts or components from China. It’s very hard to escape Chinese batteries, especially if you’re after the cheap LFP batteries which are best suited for low-priced cars. And if you’re an American or European carmaker it’s very, very hard to compete with China. Certainly on price. Also, in some respects, on battery and technology. China has all but won.

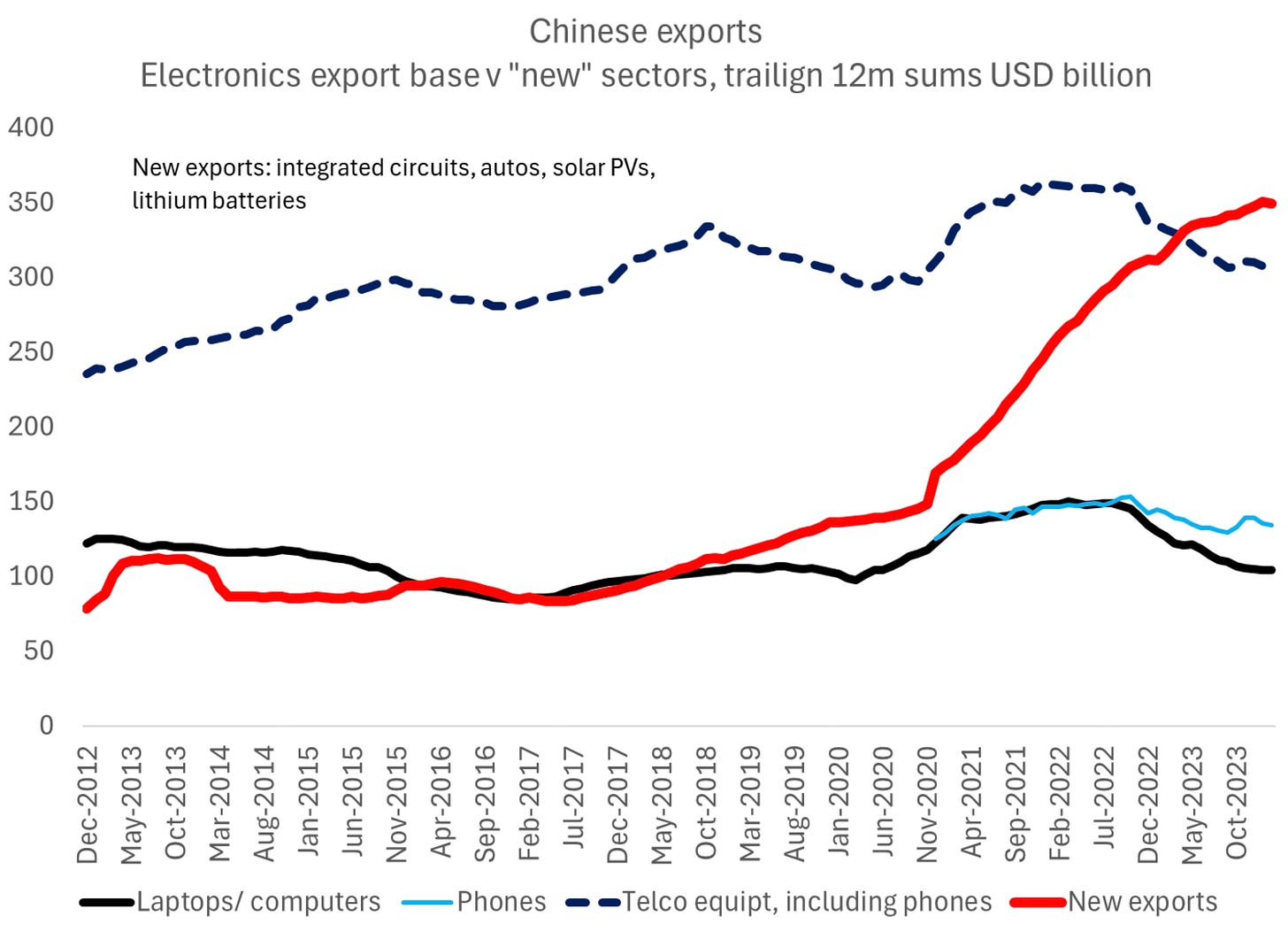

Indeed, in some respects it’s been too successful. Because China is now producing so many EVs and solar panels and so on that its domestic market is (or will soon be) completely saturated, with the upshot that global markets are/will be flooded with very cheap Chinese exports. There’s a good thread on this (with charts including the one below) from Brad Setser (who is a must follow on this stuff).

All of which raises the question: how did this happen? Why is it that the 21st century Henry Ford is Chinese and not American? Well, that’s where things get a little… political.

Because while part of the explanation for China’s leading edge on cars (you could say something similar by the way about solar panels and wind turbines and other green products too) is cheaper labour costs than you find in Europe or America, and part of the answer is China’s enormous, growing domestic market for this stuff, the rest of the explanation comes down to what we in the west tend to call “industrial strategy”.

It’s very difficult to put a figure on just how much support the central and provincial parts of China’s government have provided for their battery/car industry. But every bit of statistical and anecdotal evidence suggests it’s, well, rather a lot. The upshot is that (at least up until the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act), Western companies have not been competing on an even playing field. Indeed, even after accounting for the IRA it’s quite possible that Chinese subsidies still dwarf the American (and European) ones.

The upshot of all this is, well, a few things. First, it helps explain why it is that the equivalent of the Model T for the electric age is likely to come from China rather than anywhere else. If you are looking to buy a truly affordable electric vehicle, the chances are that car will have been made in a Chinese factory. If European nations manage to meet their 2035 goal of phasing out the sale of petrol cars, it will be in large part thanks to Chinese cars. Not European-made ones (and don’t let’s begin on where the batteries or the cathode active materials in those European cars come from).

Still: cheap cars - hurrah, right? Talk to economists (or those writing the leaders at the FT or the Economist) and they’ll tell you this is great news. China has wasted money subsidising its car industry and pumping out vehicles at rock-bottom prices then that’s surely to our benefit, right? We pay less for our cars thanks to their subsidies…?

Except, this doesn’t quite add up either. Because the flipside of this is that all those Chinese subsidies have, in the process, contributed to the deindustrialisation of large swathes of the West. Europe is desperately struggling to compete with China; its car industry looks in serious trouble. And since China is not importing more British or American goods, lots of the money it makes selling us cars is being diverted into doing other things like buying British Steel or stakes in Heathrow Airport or UK Power Networks. This can actually decrease domestic investment. And this is before one gets to grittier questions about national security and how much sense it makes to be so reliant on a country with which we have a complicated relationship.

So you see, this is not easy or comfortable. What began as a simple question about who might be the modern equivalent of the early 20th century’s capitalist giant has turned into a whole barrage of questions about the nature of modern day capitalism.

But it does help explain some of the background to the ongoing political tension between the US and China. American Treasury Secretary was in China this week, and appealed for the country to do what it can to deal with this “overcapacity” - the flooding of other markets with Chinese cars. But it’s not clear how much China is willing to do, as stifling its sector will mean higher unemployment and what might be euphemistically called “difficult decisions”.

In short, this is becoming a very big deal - such a big deal I expect to write more on this in the coming weeks. The industrial battle between the world’s superpowers, over electric vehicles, over green technology, over AI and for that matter over plain old products like steel, is hotting up.

The Material World is becoming more and more relevant with every day that goes by…

More fundamentally, subsidising cars disincentivises alternative urban structures and policies that don't have cars front and centre. Bike-oriented and walking-oriented streets might be nicer places to live and work, but we'll never know because the Chinese government is tilting the scales against creating these.

Carefully tiptoeing around the real reason China can make cars more cheaply (even before their vast subsidies) than in the west - they still have cheap energy, while we pursue the pipe dream of Net Zero. Meanwhile, even if EVs cost only $5,000 it would make no difference to all those with no visible means of charging them.