Lights Out World

Just because fewer and fewer people are working in the Material World doesn't mean it's less important. Quite the contrary...

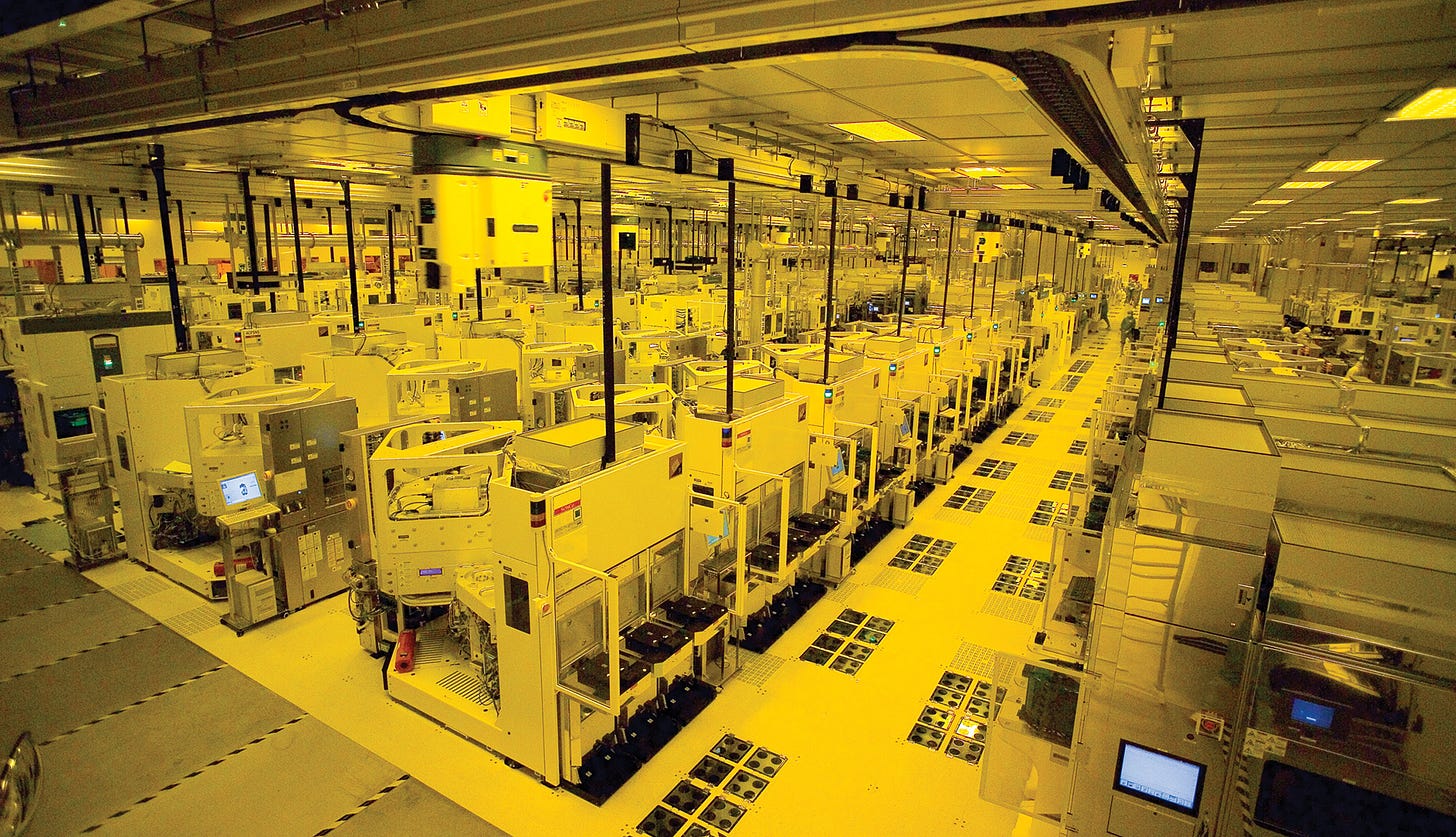

Have you heard of lights-out manufacturing? It’s the idea that these days you can have factories which can be completely operational without the need of any humans on site whatsoever.

There are lights-out fabs in Asia where semiconductors are made these days, the silicon wafers whooshing from one machine to another in little shuttles (FOUPs, they’re called) where they never even have to touch the purified air of the factory. There are lights-out factories where electric razors are made and where robots are assembled, before themselves becoming part of lights-out factories to make other products.

This all sounds rather dystopian, no doubt. But the point is it’s not some vision of the distant future. It’s already here!

As you’ll know if you’ve read Material World, the defining feature of so many of the places I visited was the absence of people. The vast room I describe where 98 per cent of Britain’s chlorine is made is manned by maybe one or two people. I spent some hours wandering around a gas terminal in Qatar and barely seeing another human. On a dock at Teesside it became very difficult to tell the difference between the industrial units which were working and those which had been abandoned some years ago. It is a strangely empty place.

One’s natural reaction to this is usually revulsion - and understandably so. We humans rather baulk at the idea of fellow humans being put out of work. Once upon a time that cell room in Runcorn had many more people working in it; something similar went for the world’s natural gas installations and other factories. Once upon a time a large copper mine like Chuquicamata would have had thousands if not tens of thousands of people working away, hammering at surfaces and lugging rocks. Today a single person can move 400 tonnes of rock with the help of an ultra class truck.

But there are some important positives to this dystopic vision. The first is that many of these jobs, nostalgic as we may be about them, were tough, dangerous jobs. Working in a mine or on an oil rig is a risky thing to do - even today, even though we’ve dramatically reduced the number of accidents happening there. Fewer people doing these jobs also means fewer deaths.

One of the consequences of this is that there are fewer and fewer people working in these fields. That means fewer people working in manufacturing - and so needing to find new work. Politicians and economists talk about these “displacement” issues a lot - for good reason. They’re important and are part of the explanation for why many parts of the UK and US feel “left behind.”

However, there’s another broader consequence I think we talk less about. Because there is a far smaller proportion of the workforce in these sectors there are fewer people who are aware of what it takes to make the stuff we take for granted. There’s a gap in the public consciousness.

Consider another of the positive sides of the “lights out story”. A century and a bit ago more than half the workers in the United States worked in agriculture. Today it is barely more than one per cent.

Back in 1800 it took, on average, about 150 hours of human labour to produce a hectare of wheat. Today, thanks to steel ploughs, modern fertilisers, diesel engines and combine harvesters guided in some cases by GPS (and equipped with multiple semiconductors), it takes less than 2 hours to produce a hectare of wheat. And that hectare is even more packed with viable crops.

This is one of the greatest success stories of the modern world! We are able to produce staggering amounts of food - and for that matter base metals and plastics and manufactured products - with only a fraction of the amount of labour.

Yet read a magazine like the Economist a few times and you will invariably read about how agriculture is a “low productivity sector”. This is patent nonsense. Yes it’s a low output sector. It doesn’t contribute as big a slice of GDP as it used to - unlike professional services or finance or social media. To put it another way, we don’t spend as much of our money (that, after all, is what GDP is counting) on agricultural products.

But… that’s kind of the point! The great achievement of agriculture over the past few decades has been to produce ever more food at reasonable prices with ever lower inputs. We don’t have to pay an ever increasing amount on basic foodstuffs - so we can spend that money elsewhere, often on things like haircuts and other consumer services (driving up their prices).

It’s entirely thanks to agriculture’s phenomenal productivity leaps that half of us no longer work in the fields, and so have time to twiddle our thumbs and read The Economist rather than tilling the land all day.

And these productivity improvements continue. Look, above, at the relative performance of output per worker in France over the past few decades. It’s agriculture and then manufacturing which are the strongest performers - in large part because of this “lights-out” effect. For better or worse, they can produce the same stuff (be it a kilogram of grain or of copper) with fewer people and lower costs than ever before.

Something similar goes for the UK:

The point here is not to romanticise manufacturing. Many of the jobs that have now disappeared were not great jobs. They were often dangerous, dirty jobs. But by the same token they were often quite important jobs. These workers might not have contributed an enormous amount to GDP but they did often provide humankind with products and materials that very tangibly improved their lives.

Being sniffy about manufacturing and agriculture just because you don’t work in those sectors (and most of us these days don’t) is to lose sight of the productivity miracles that have landed us in the world we inhabit today.

We can do without social media; we can even just about do without haircuts (as we learnt during the pandemic). No-one would die if much of the sector I work in - journalism - was suddenly wiped out by a freak phenomenon (dare I say, it’s possible the world as a whole might actually be happier). Same thing for much of the professional services sector.

But we simply cannot do without fibre optics or copper wiring or concrete or bleach or plastic piping. This stuff just matters in a way much of the rest of the economy doesn’t.

That was one of the things drawing me towards the Material World. The point of the book was never to say this stuff is all-important or that it is the be-all or end of all of the modern world. It isn’t. But it clearly matters more than the conventional wisdom, and the typical metrics of economic success, would have you believe.

It contains wonders we could all spend a little more time contemplating.

The fewer people who are working on these sites, or in these industries, the smaller the talent pool from which experienced management can come: virtually all businesses really need this hands-on experience. The water industry seems a classic of this point at present: so few people are involved in the collection and processing that it's nearly all so-called professional management, and look at what a great job they've done for one of our most precious materials!