Jan Czochralski: the forgotten hero of the silicon age

Today's silicon chips are all made using a technique invented by this scientist more than a century ago. But his life ended in ignominy and tragedy

The Oberspree Cable Works is an enormous red brick 19th century factory overlooking the river in Berlin.

Like most surviving warehouse buildings of that era, it has today been refashioned into trendy live-work units occupied by tech start-ups producing apps and products for the internet age. Yet few of these young entrepreneurs are aware of the significance of what happened here just over a century ago, when a scientist made a discovery which would help usher in the computer age.

That scientist was Jan Czochralski, a mild-mannered Polish researcher working for AEG, the German electrical company which began as an offshoot of Thomas Edison’s international business empire but is better known these days for the kitchen appliances which wear those initials. Czochralski’s job was to experiment with materials in the hope of finding new formulations which could improve the electrical cables and machinery of the early electrical age.

One night in 1916, after a long day of experiments in his lab, Czochralski was at his desk writing up the results, occasionally replenishing his fountain pen in his inkwell.

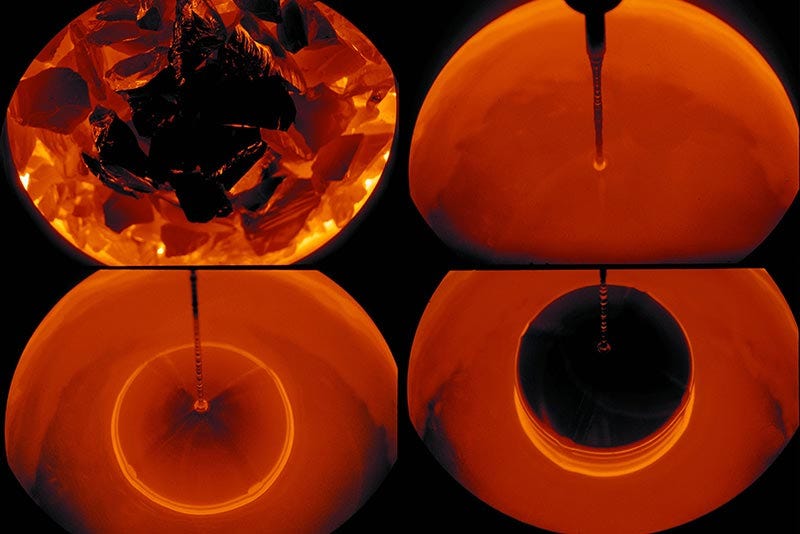

In an absent-minded moment, he accidentally dipped his pen not into the ink but into a nearby crucible of molten tin, which had been cooling off after one of the experiments. Realising his mistake he pulled his pen out of the liquid metal and noticed with astonishment that the nib appeared to have grown a long, thin thread of metal. When he came to examine the thin strand of tin, he noticed something even more startling: it was, quite literally, perfect.

The Czochralski method, as it has become known, occupied a relatively obscure corner of the metallurgist’s repertoire until the early days of the transistor age, shortly after John Bardeen and Walter Brattain had made the world’s first semiconductor at Bell Labs in December 1947.

But in the early 1950s, a former Bell Labs colleague of theirs, Gordon Teal, rediscovered it and used this process to grow germanium and, even more interestingly, silicon crystals.

At the time, the conventional wisdom was that silicon transistors would be impossible for years, but Teal, then working at Texas Instruments, showed that by slowly pulling a crystal of silicon out of a molten bath of the stuff, you could create a single crystal which could be sliced into perfect wafers. The silicon age had begun.

Teal and Czochralski, it’s perhaps worth adding, rarely feature in most stories of how computers came to be. We hear a lot about the other folks at Bell Labs, about the moment Brattain, Bardeen and Shockley produced the earliest transistors or the moment a few years later when they won the Nobel Prize.

Czochralski never received such recognition - or anything like it. His life was dogged by indignity.

Some years after inventing the process that still bears his name, he moved back from Berlin to his native Poland. The return was disastrous. His fellow faculty members at the Warsaw University of Technology questioned his qualifications.

He was repeatedly quizzed about his nationality; was he Polish or German? When Germany invaded in 1939 it only made matters worse. He was accused - wrongly, it seems in hindsight, of collaborating with the Germans. Afterwards, in 1945, he was arrested and charged with betraying the Polish people. He won the case but lost his job and - the ultimate indignity - his name was expunged from the list of professors at Warsaw.

Even in retirement he found no respite. Hounded repeatedly by the secret police, he eventually succumbed to a heart attack in 1953, shortly after a raid by a troop looking for evidence that he had hidden away some US dollars from the sale of his house. Had he lived only another year he might have heard news that thousands of miles away in the United States, his process had been adapted to create silicon wafers for semiconductor manufacture.

But by then Jan Czochralski had already been buried in an unmarked grave.

His technique to create perfect crystals is still the bedrock of how we make the silicon wafers that later become silicon chips. Yet few have heard of this man, or are aware of the story behind his invention.

Just for your information, his grave was renovated few years ago, you can see it here -> https://pomorska.pl/grobowiec-jana-czochralskiego-swiatowej-slawy-naukowca-z-kcyni-po-renowacji-jest-tez-tablica/ar/13432171

Great but somewhat tragic story. I always enjoy stories of serendipity in science although it always has to be noted that it often takes an observant person open to unusual ideas to recognize the significance.