How not to use your time as an energy superpower

Some countries use their energy riches to invest for the future and support the next generation. Then there's what Britain did.

The other day I wrote a review of Will Hutton’s new book for the New Statesman and in the process I got thinking…

Part of the premise of the review (and, I felt, the Hutton book itself) is that while we (policymakers and journalists especially) often fixate on short term problems or challenges, invariably our fate is more likely to be determined by invisible, long-term forces we rarely spend much time talking about. Beyond the headlines about this or that recession, or even seemingly seismic policy moments like Brexit or the election of this or that government, often other stuff - culture, demographics and so on - matters even more.

And of those invisible, potent, under-discussed forces, the one I find myself thinking about an awful lot at the moment is energy. As you know (especially if you’ve read the book) I’ve come recently to think that energy is more or less everything.

It’s certainly everywhere. All economic activity is, one way or another, a form of deploying energy to do stuff. Yet we typically understate the importance of energy to modern economics. I think, for that matter, that economists’ inability or unwillingness to consider the effect of energy on the price of essentially everything was part of the explanation for why they missed the scale and depth of the inflationary spike we’ve been going through. Only when you internalise the fact that, for instance, all food prices are a reflection of energy prices (energy in the fertilisers, energy in the food production costs, energy in the shipping etc) do you realise that it’s essentially all one and the same thing.

Anyway, most of the time we don’t think about that kind of thing, because we don’t have to. Energy prices are usually relatively stable and so we tend to ignore them. But then every so often there’s a seismic shift which forces us to realise how much this stuff matters.

The example I gave in the review was Germany. For years the conventional wisdom was that the German economic model was the one to be admired and, if possible, emulated. Then Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, gas prices went through the roof and everyone suddenly realised what should long have been staring them in the face: the German industrial “miracle” was predicated in large part on cheap gas piped in from Russia, to fuel car factories and feed chemical chemical plants.

The German epiphany was so rapid, so brutal, that it is forcing some deep thinking there (though some would say: not quite enough) about what to do next. The country is going through a rapid, aggressive deindustrialisation which I think we’re only beginning to get our heads around.

But I think something similar (if only more gradual, more invisible) also applies to the UK. I can’t help but feel many in the UK have been deluding themselves about energy - about its importance, and about the fact that up until quite recently the country was living through a period of relative energy plenty. But that period might already be over. And we need to start talking about it.

We forget these days that for most of its history, Britain was disproportionately energy-rich. Stinking energy-rich. Part of this country’s economic might was hinged not just on our institutions or our geography or so on, but on the fact that we had rather a lot of energy.

First there was coal. As I wrote in Material World, England was the first country in the world to exploit the world’s first great fossil fuel in vast quantities - partly in an effort to escape a much-feared ecological catastrophe (deforestation). A significant part of the explanation for why the Industrial Revolution happened in England and not, say, France comes back to this. It broke free from the thermodynamic constraints of fuels one had to grow by burning fuels one could mine.

Of course, these days coal is the bogeyman - for understandable reasons - but coal, let’s not forget, was also what helped deliver Britain extraordinary gains in productivity, living standards and incomes in the 19th and early 20th century. And not only did Britain lead the way in burning coal for all sorts of industrial processes (refining steel and other metals, making chemicals, glass, fertilisers and so on - more in The Book), it also led the world in getting coal. With its rich, accessible deposits of anthracite, Britain was, at the turn of the 20th century, the world’s largest exporter of energy. It was the “Saudi Arabia of 1900”, as David Edgerton once put it.

Britain was, in other words, what you might these days call an “energy superpower”. Of course, as the 20th century wore on others caught up; Britain’s share of global coal production (and consumption) declined. But even as oil muscled in as the up-and-coming fossil fuel for the global economy, Britain retained its position as an energy superpower in other respects.

It was in Britain that in the 1950s, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station was built at Calder Hall. For a period it looked as if the UK would have more reactors than any other country in Europe (this of course was long before France began its push for nuclear power). And while for a while Britain was desperately reliant on other countries for crude oil, then along came another stroke of luck.

The discovery of North Sea oil in the 60s and 70s meant the UK became a considerable force in petroleum - not quite Saudi but surprisingly close. I think we sometimes forget how much oil the North Sea was pumping, back in its prime. For a period in the 1980s, the UK was the world’s fifth biggest oil producer. For much of the 1990s it was the world’s fourth biggest gas producer. Britain wasn’t an also-ran. It was a bigger force than nearly any single OPEC member.

North Sea oil meant Britain could depend on a reliable supply of oil and natural gas for decades. The country quickly constructed a national grid for gas, changing the way most homes were heated. North Sea oil and gas fed the chemicals works and refineries in Teeside and Humberside, helping cement the country’s position as a chemical and pharmaceutical giant.

Plentiful energy didn’t necessarily mean cheap energy: since oil is globally traded, the price was determined by global factors. But the fact that much of that energy was coming from the UK meant that when prices were high the UK could at least offset the added costs with added profits. Nor did this just benefit the oil companies. North Sea producers have always had to pay quite hefty taxes (some would argue not hefty enough - but they are definitely not trivial) into the Exchequer. And that meant the rest of the country benefited too.

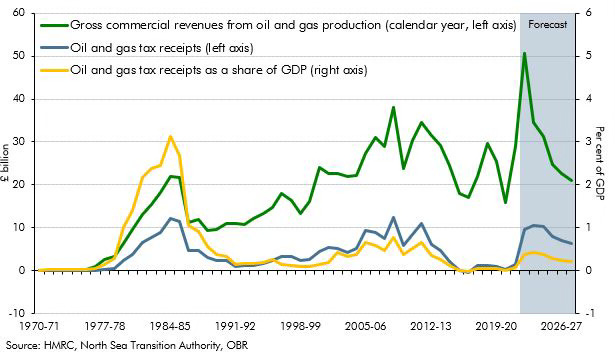

This OBR chart tells the story quite well. Look at the yellow line. Back in the mid-1980s, North Sea oil receipts were equivalent to more or less 3 per cent of GDP. This is massive! It was enough to finance the entire transport and housing budgets. Indeed, it was considerably more than the government earned from all council tax and corporation tax (the non-North Sea bit) in that year.

And remember, this windfall came from more or less nowhere. It was luck. Thanks to this stroke of luck Britain’s public finances looked considerably better than they would otherwise have done. Actually they still do, even today. While the revenues peaked in the mid-1980s, they didn’t disappear.

In fact, they stayed high throughout the 80s and 90s and even today the North Sea revenues are still considerable. At £10bn in 2024/25 this country earns more in tax revenues from the North Sea than from inheritance tax; it’s equivalent to about a penny and a half off income tax.

I’m struck by how often we forget this; or how quick people are to assume that North Sea oil is essentially finished. It’s not. Yes, it’s down considerably compared to the 1980s and ‘90s. Yes it’s no longer enough to satisfy our demand. And most geologists think the direction of travel is downwards in future - even if there’s more exploration and production in the coming years. But even today, the UK still produces the equivalent of about half its total oil consumption (see the chart below).

Perhaps part of the reason people have always paid so little attention to the oil sector is that it’s quite literally out of sight - far offshore in the North Sea. A comparatively small (but very experienced) subset of people, mostly located in the north east of Scotland, work in the sector. In other words this is not like the coal industry, which used to employ hundreds of thousands of people across various parts of the UK.

Another theory for why we don’t pay enough attention to our energy plenty is that successive UK governments rather encouraged us not to think about it. They almost pretended nothing had changed, even after Britain had become an oil superpower. They didn’t dramatically change the nature of economic policy to reflect this new plenty. They carried on regardless. And that brings us to one of the great tragedies of modern politics.

None of the governments presiding over the North Sea boom actually put aside any of those billions of pounds of revenues. Norway built up an enormous sovereign wealth fund with its surplus oil revenues. There is no reason Britain couldn’t have done likewise. Instead, all the money (roughly half a trillion in inflation-adjusted terms) generated from North Sea taxes was funnelled back into the Exchequer and used for day-to-day spending.

This would be somewhat more forgivable if the the UK government had used all that money to invest in the country’s physical or intangible capital. But at the very same moment that North Sea tax revenues were booming in the 1980s, UK investment spending was being cut. The most egregious period here was in the mid-1980s: for eight years, total North Sea oil revenues actually exceeded the total amount the government was investing in improving the country for the future.

Instead of using this one-time windfall to improve Britain’s infrastructure or to create a rainy-day fund the Thatcher government frittered it away on current day-to-day spending, providing a short-lived mirage of prosperity. Now some would argue that this was a price worth paying to help lift British prosperity. But I’m not sure we fully appreciate how much of this was helped by North Sea oil.

Nor is there as much of an industrial legacy from this period as there might have been. For much of the post-war period moments such as these were seen as opportunities to build domestic powerhouses. When the social security system was computerised in the 1970s, those paper records were replaced with British computers. This period of British industrial activism has gone down in infamy (British Leyland, picking winners etc etc).

But it’s striking to note that by the time the North Sea was coming to the fore, the fetish for industrial strategy was waning. There was no effort, for instance, to create a national oil company, as Norway did, or to stipulate that, say, offshore services or structures had to be provided by UK businesses. Whatever you think about the wisdom of this, there are lasting cultural implications. Unlike in Norway, with its massive state oil firm and similarly massive public oil fund, you could be fooled into thinking the North Sea simply never happened at all.

But it did. Honestly. For a long time, Britain was an energy superpower. Who knows, it could be again in the future…

Excellent piece Ed. It is underappreciated how oil and gas wealth supported Thatcher to win three general elections (more so than many of her economic reforms). Though it is instructive that the (Labour) government in the 1970s knew that oil and gas money would transform public finances, even while applying to the IMF - it was just a question of time before revenues began to flow. As you note, Norway took a different path with its sovereign wealth fund, while France built nuclear power stations. Gas-rich Britain built a world-class gas infratructure and used gas in power and central heating. Without that oil and gas wealth in the 1980s, Britain might have followed France but the Howell programme was scaled back by Nigel Lawson.

Ed of course! Energy is what does all the work. Industrialisation is a giant metabolism needing feeding. History? I was in my 40s in the 1980s. Like the balance between capital and labour, the global balance between energy suppliers and users needs to be negotiated.

By 1970 the USA used more petroleum than it could produce and its Lower 48 production was declining. The ME took advantage of the shift in global balance.

France reacted to the 1973 'oil shock' by building nuclear. (It did have privileged access to uranium and a dirigiste mind-set.) Denmark shipped in coal and built CHP units round its coast. UK already had methane to replace coal gas. "The process of converting the entire GB market from town gas to lower-cost natural gas from the North Sea began in 1968 and was largely completed by 1975." Then there was N. Sea oil. When my young neighbour in Scotland went to work on the early rigs they were 'American'. It was all BTUs, none of that metric rubbish.

Thatcher?

You can't divorce her from Reagan and those new economists. She got lucky with the Falklands or she likely would have gone early because of recession caused by a highly unstable exchange rate. Britain de-industrialised fast during the 80s. It was shattering for old industrial areas and employment by the early 90s. (I witnessed it.) A lot of revenue from the N. Sea it seemed propped up the nation as we 'modernised'. Then it was ‘La La Land’ until 2005 and the financial chickens coming home after 2009. It is a different world from now on. Many thanks for all the info and conversations you have developed. Never mind the weather, I agree, buy the new text book. Smile.