Globalisation is a far, far bigger deal than you think

What an obscure factory in the English Midlands tells you about the way the world works

A couple of years ago I visited a factory on the outskirts of Birmingham belonging to a company called Brandauer.

Despite the German name, this business’s story begins in Birmingham in the 19th century, when, under its French-German owners, it began to manufacture the nibs at the top of fountain pens.

At the time this was a big business: metal nibs were replacing quill and ink, and since writing with ink on paper was one of the main methods of communication, Brandauer fast became one of the most important companies in the communications sector.

These days very few of us write with fountain pen and ink, but it so happens that being able to press super-thin metals with extreme accuracy (which is ultimately what the company did) is a pretty handy skill these days. Today Brandauer no longer makes fountain pen nibs but it does press metals into micron-accurate pieces - in vast quantities.

So while you probably haven’t heard of the company you have almost certainly used one of their components in the past few days.

There are all sorts of Brandauer components inside all sorts of everyday items. Those metal cutters at the top of dental floss packets? There’s a good chance they were pressed and churned out of the Brandauer factory in Birmingham. Same thing for some of the metal parts in pacemakers. Or consider the N95 face masks which became ubiquitous during the pandemic: the soft metal nose clips were mostly made by Brandauer. I could go on, but you probably get the point. This place is an important little cog in the global economy.

If you’ve read Material World you’ll already have encountered plenty of other companies like this: firms no-one’s heard of which happen to be the most important producer of x or y mineral or machine or part, upon which we quietly depend for this or that part of our lives. Brandauer didn’t make it into the book but I often think back to my visit there, when I was shown a tiny little piece of metal being churned out of a machine.

This little piece of metal, small enough to balance on a fingernail, was pressed and plated and then sent off to another company on the other side of the world who make the rear view mirrors for cars. There it would become an electrode in the circuitry that helps the mirror to dim automatically when there’s a sudden glare.

But what was so striking wasn’t the part itself, so small you could easily miss it, but the sheer quantity being turned out of this anonymous factory in the Midlands. For this place produces a whopping 55 per cent of all these electrodes in the world. If you have a car with a dimming rear view mirror, it’s more likely than not that it dims thanks to this little piece of metal made by Brandauer.

It’s quite a useful example, this, because it tells you something important about the nature of the modern global economy. While it’s tempting to assume that for any given component there must be hundreds of different competitors vying with each other, in practice it’s not quite like this. The market for rear view mirrors is actually considerably more concentrated than you’d have thought. Same thing for the market for the electrodes that go inside them.

In many sectors this is the way globalisation works: a small handful of companies are responsible for the world’s production of a single widget or item which then gets assembled inside someone else’s car or computer or face mask.

In a sense it’s the ultimate extension of Adam Smith’s principle of the division of labour. Smith wrote about a pin factory where “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head” and so on. And by dividing up the tasks of pin-making and specialising in one specific role, ten people could turn out tens of thousands of pins in a day as opposed to the 200 or so they could have made if each person was charged with making an entire pin from start to finish.

As I wrote in a column in The Sunday Times not long ago, a good example of this these days is the car industry, where a car manufacturer is better thought of less as a manufacturer than as an assembly point, where thousands of items, made mostly by other companies, are fitted together and turned into a motor vehicle.

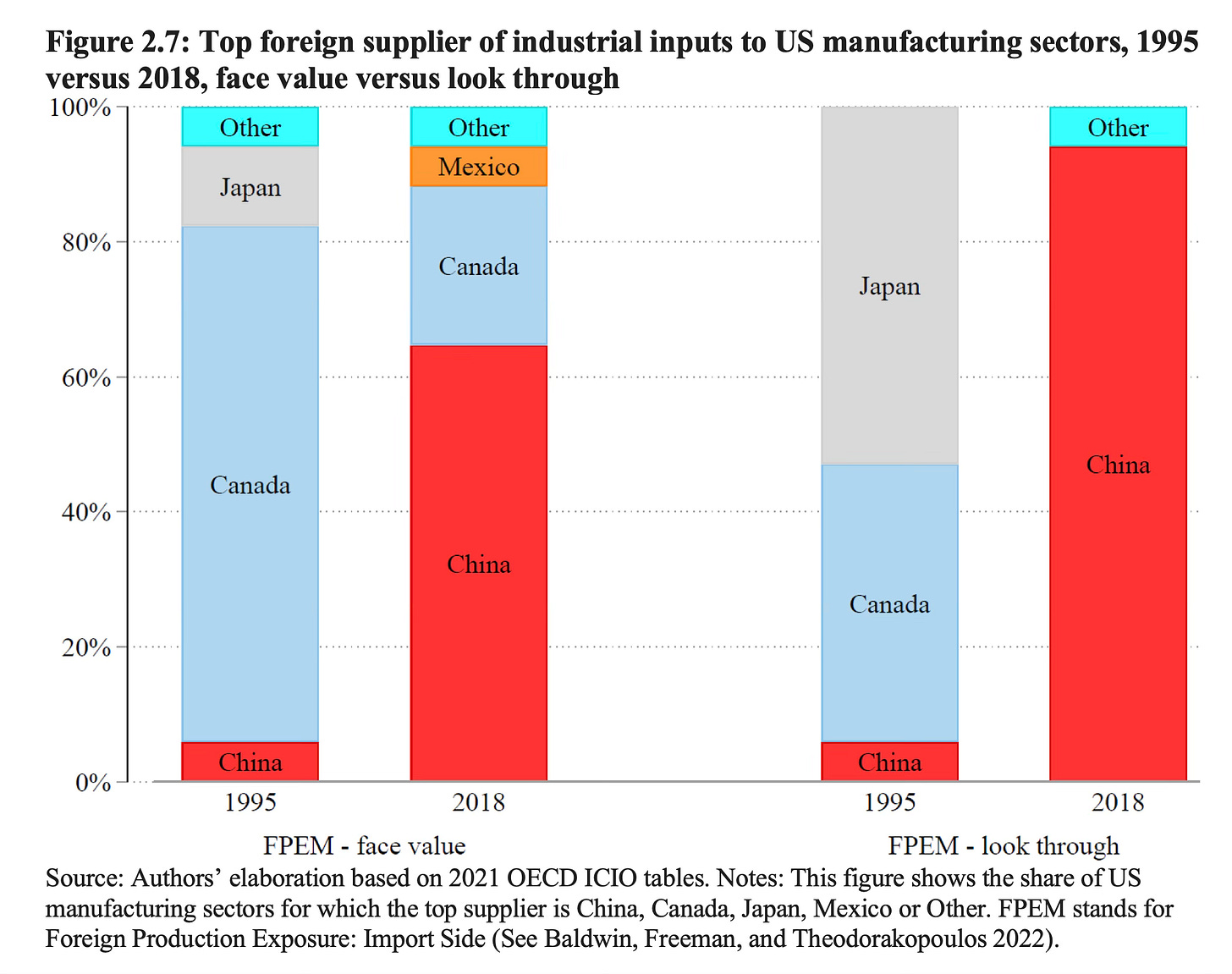

According to a fascinating new paper from Richard Baldwin, Rebecca Freeman and Angelos Theodorakopoulos, roughly 75% of the cost of the average car comes from these so-called “intermediate goods” which then become part of your finished Ford or Land Rover. The Baldwin et al paper makes some pretty profound points, among them the fact that when you peer at the world through this lens, the importance of China is far greater than when looked at through conventional prisms.

The chart above is the key one. First look at the two bars on the left hand side. This is what conventional trade statistics tell you about the dominance of China as a supplier to American manufacturers: up from being the main provider of inputs to about 5% of sectors in 1995 to just over 60% in 2018. That’s pretty striking. But now look at the two bars on the right. These are the authors’ measure which includes all those intermediate inputs (a far more complex picture) and it turns out China is the main source of these goods for about 95% of all American industrial sectors.

One obvious takeaway from the paper: whoa, America is far more reliant on China than it thought. But actually this underplays the complexity. Think back to our Brandauer electrode. The chances are that it was made of metals which were originally refined in China (I’m guessing here, but given China is the world’s biggest metal refiner this is not implausible). Those metals were then shipped to the UK where they were turned into the micron-accurate electrodes I saw being turned out of the machines in Birmingham. Then they were shipped back to another factory, probably in China, where they were put inside a rear view mirror.

When this rear view mirror was finally shipped to a US factory to be fixed to the windscreen of a Ford, it will have looked like a Chinese intermediate input, but that Chinese product was in turn dependent on a manufacturing process happening in the UK. Now imagine the same thing for pretty much every tiny widget and intermediate product going into our cars or our smartphones or indeed anything else.

This is just the way the world works. It is far more intertwined than you might have thought. While there is no doubt that, as Baldwin writes, China has become so dominant in this invisible part of the manufacturing world that it might well be considered “the OPEC of industrial inputs”, sometimes what looks like a Chinese product is actually a tapestry of ingredients produced elsewhere.

And that’s part of the explanation for how we have managed, over time, to bring down costs and improve our living standards. In just the same way as Adam Smith’s pin factory divided up the work so a single person had the responsibility for one minute part of the manufacturing process, today across the globe work has been divided up between thousands of companies like Brandauer, world leaders in making a particular component you’ve never heard of.

But the flip side of this story is one of risk. Each of these companies represents an important micro pinch point in the global economy. If we are now living through a new Cold War, and if that Cold War begins to affect global trade (this might already be happening) then the consequences go far beyond the sexy stuff like semiconductors and battery manufacture. It potentially affects the production of pretty much everything.

PS Apologies it’s been so long since I posted an update. Things have been busy. And I suspect they’ll get busy again soon. But I’ll keep posting here with extra thoughts on the themes about the Material World. In the meantime, here is a film I made recently for Sky News about water. You might enjoy it…

Major points taken of course, but fountain pens were later. When I started primary school we still had ink wells in our desks (and inky fingers; smile).

'Globalisation' was the 'next big thing' to add to 'economies of scale'. and fossil fuel energy still cheap enough to scale-up? China electrified on vast domestic coal expansion (a one off). And the digital world enabled vast complexity.

What is the 'next big thing' and where is the cheap (and 'energy cheap') fuel to come from? And materials?

PS liked your film about British sewage ... hope 'we' can afford it ... lots of issues ... toxics as well as ordinary NPK flushing through the system ...

This reminds me of the realisation back in the early 2010s that every iPhone shipped from Foxconn was probably a net import into China on a passthrough basis, once you reckoned up the processor fabbed by Samsung or TSMC in Taiwan or Austin, TX, the modem from Qualcomm, the Bluetooth and WiFi radios (from CSR to begin with), the touchscreen from Corning, plus the use of the Apple-specific machine tools and a bunch of intangible contributions.