Does it really matter if we can't produce "virgin steel" anymore?

In short, not half as much as people might have you believe. But that doesn't mean there aren't some real problems with Britain's plans to ditch all its blast furnaces.

I had been meaning to post something about this once I’d got the general election, in which I’m quite involved in my day job, out of the way.

After all, here in the UK we’re on the brink of an important turning point, with plans now underway to close the country’s last remaining blast furnaces: the two at Port Talbot, which featured in chapter 8 of Material World, and the two still in operation at British Steel over in Scunthorpe.

This has sparked all kinds of consternation. Most notably, a lot of people are fretting about the significance of this country - the country which invented modern steelmaking - no longer being able to make “virgin steel”.

If you’ve read the book you’ll already know this, of course, but the distinction here is more or less as follows. Most of the world’s steel is made in blast furnaces, which take iron ore and melt it down alongside coking coal and a few other ingredients to produce a pure-ish form of iron (pig iron) which can then be turned into steel (an even purer iron alloy). Making “virgin steel” this way is very, very carbon intensive.

The other main way steel is made these days is in electric arc furnaces (EAFs), which take scrap steel and a few other ingredients and use a massive electrical current to melt it down. The end product is recycled steel. And the plan at Tata and at British Steel is to replace their blast furnaces with electric arc furnaces, thus reducing their carbon emissions and making them compliant with Britain’s net zero laws.

Anyway, I had already done a bit of research on whether this virgin steel issue was really such a big deal, but then the election came along and I parked the topic. But just the other day the management at Tata Steel UK, which owns the Port Talbot plant these days, said that if a strike currently being planned by union members at the site were to go ahead, they may need to close down the blast furnaces not in the autumn but as soon as this coming week. In other words, this historic moment might all be about to happen round about now.

So I figured I should probably dash down some thoughts, even if they are slightly less polished and slightly more pocked with holes than they would be had I written this when I wasn’t in the middle of pre-election psephology revision.

Because it turns out that many of the arguments you see trotted out on social media about why Britain desperately needs virgin steel are a little less compelling once you look into the details. Even so, as we’ll get to in a moment, there are good reasons to remain nervous about spontaneously allowing all these blast furnaces to close, even if they’re not the arguments you most often hear expressed.

And those arguments mostly revolve around two poles: that closing blast furnaces will a) leave us desperately dependent on imports and b) will mean we can’t make the advanced varieties of steel we need in future. Both arguments are a bit suspect.

a) We’ll be too dependent on imports

One of the worries often expressed on social media is that without the ability to make virgin steel the UK will be especially exposed if, say, there’s a war. We won’t, goes this line of argument, be able to make all the grades of steel we currently can, leaving us perilously dependent on imports from heaven knows where.

But this argument is clearly not quite as watertight as it might sound in practice. After all, even the virgin steelmaking at Port Talbot is dependent on imports from elsewhere. We stopped mining iron ore in this country many decades ago, meaning these days we need to import iron ore from Sweden, Brazil and sometimes Australia. We import coal from Europe and further afield, as well as other ingredients that come in from overseas. So the notion that having a blast furnace makes you more self-sufficient isn’t as straightforward as you might have thought.

Nor, it’s worth saying, was Britain ever totally self-sufficient for this stuff in the past. Back in the run-up to WWII the UK was reliant on iron ore imports from the Kiruna mine in Sweden to make its own steel. Indeed, much of the northern front between the Allies and Nazis, over control of Norway, had this economic subtext. Both Germany and the UK needed Swedish iron in large quantities, to turn into weapons.

Actually, in a sense, shifting from importing iron ore to recycling steel will actually make the UK less import dependent - in that the main ingredient going into electric arc furnaces will be scrap steel we have here in the UK.

This is a point worth underlining. Right now we throw away roughly 7–8 million tonnes of scrap steel per year - from old cars, old machinery, demolished buildings and so on. This is actually considerably more than the total finished steel output of our industry (5.6m tonnes). At present, the vast majority of this scrap steel is exported overseas to countries like Turkey, where it is melted down in their electric arc furnaces. If the UK had more arc furnaces (which is the plan) then we’d be able to recycle more of this ourselves and the loop will be closed.

So while it’s certainly true that the UK will become dependent on imports of certain products we’ve typically made here (the most obvious one being direct reduced iron or pig iron, the kind of thing that comes out of blast furnaces, which you still need a bit of for electric arc steelmaking) in another sense, the overall level of dependence might actually come down.

b) You can’t make advanced steels with electric arc furnaces

This is one of those arguments that used to be true. In the early days of mini-mills, as electric arc furnaces are sometimes called in the US, the steel being outputted was of considerably worse quality than the stuff that emerged from primary steelworks. It was fine to use as the rebar in reinforced concrete but not good enough for advanced uses.

And the argument still lives on. For years its strongest proponents were, ironically enough, blast furnace steelworks like Port Talbot. Don’t invest in those silly electric arc furnaces, they’d say: the best steel, the strongest steel, can only begin its life in a blast furnace.

Except that these days that’s patently not true. For evidence, consider the UK itself. The very best grades of steel made in Britain these days are made not in blast furnaces but in electric arc furnaces.

The steel that goes into aircraft landing gear - some of the finest grades in the world - is made in the electric arc furnaces at Rotherham. The steel used to make nuclear submarines and, for that matter, parts for nuclear power stations is made by Sheffield Forgemasters in electric arc furnaces.

That we’re able to make such high quality steel in these furnaces is partly a consequence of boring stuff like managing the flow of scrap into the EAF better, partly due to more careful measurement of the ingredients going into the melt. But the upshot is it’s no longer the case that you can’t make advanced steels in electric arc furnaces.

Indeed, the real issue Tata is wrestling with at Port Talbot is not so much whether it can make advanced steels without recourse to a blast furnace but whether it can turn out the relatively cheap rolled steel it makes that goes into some of its packaging products like cans, and to do it at a sustainable rate.

Tata reckons it can already make 90 per cent of its output with EAF steel. Talk to others in the industry and they reckon actually you can make 100 per cent of grades of steel in electric arc furnaces, although for some of those steels you’d need to replace scrap steel (which can have impurities) with direct reduced iron steel. Come to mention it, if you simply filled an electric arc furnace with DRI rather than scrap then technically speaking you’d be producing “virgin steel” rather than recycled steel. So even without any blast furnaces we can still, technically at least, make virgin steel.

But…

Having said all of the above, I don’t feel especially relaxed about the UK shutting down all its blast furnaces so quickly, all more or less at the same time. For one thing, it would be continuing a pattern the steel industry seems long to have followed, of putting all its eggs into one basket.

For a very long time, the UK was unusual among developed economies in being so reliant on blast furnace steel. Whereas the majority of steel in the US is already produced by electric arc furnaces, the UK had, up until recently, only a small fraction of recycled steel. We were all in on blast furnaces. Look at the red bar here:

Now the plan is to go all in on electric arc furnaces. The chart above will be more or less reversed, with the UK bar going all the way from the bottom to the top. It’s a dramatic shift and one which no other developed country has undergone.

Even leaving aside the implications for employment (blast furnaces and the initial stages of primary steelmaking employ more people than most other forms of steelmaking), this abrupt shift has a few implications.

Let’s say there was an unexpected breakthrough in carbon capture technology, which suddenly made it far, far more effective and cheap than at present (while CCS has invariably disappointed, it’s actually not crazy to imagine that AI could help scientists come up with far better chemicals and membranes to make it really viable). That would mean all of a sudden blast furnaces were far less troublesome, environmentally, than they are at present. Indeed, since there are few other sites with as concentrated a stream of carbon, it’s hard to think of any better places to carry out carbon capture.

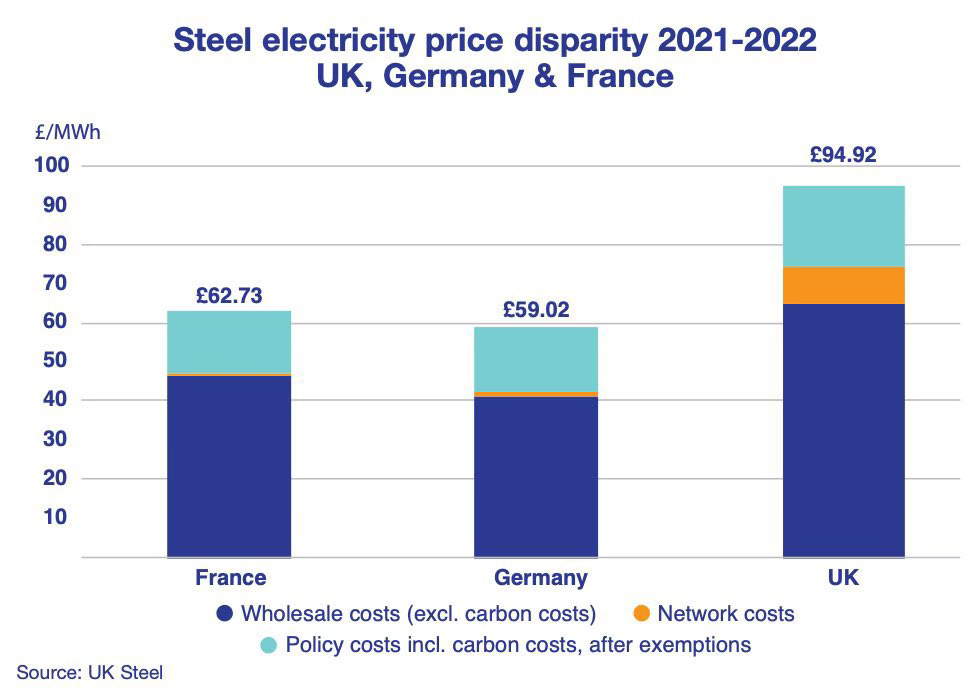

Diversity in production is helpful in other respects too. One of the main challenges for UK industry is that energy costs are so high here. That’s especially clear when it comes to power, which is more expensive than in most other developed economies. Those high power costs are part of the reason why people have been so reluctant to build electric arc furnaces here before. They are really, really expensive to run.

It’s not clear those high power costs are about to ease, meaning if we’ve committed 100 per cent to electric arc steel then all of our grades of steel will be more expensive in future. In the absence of a carbon border adjustment, the temptation will be to import even more steel from dirty blast furnaces in China.

Finally, there’s the fact that electric arc steelmaking is hardly a new pathbreaking technology (nor, by the way, does it produce entirely carbon-neutral steel). The really exciting work on decarbonisation in steel is occurring in countries like Sweden, where they are investing in hydrogen DRI plants, and in the US, where they are working on technology which could use electrolysis to produce virgin steel, much as it’s used to produce aluminium today.

Now there are still enormous hurdles for these technologies to overcome. Even so, it’s quite striking that Britain, the country which invented modern steelmaking, is essentially committing itself to a mature model of steelmaking which is many decades old. In a parallel universe, Tata could have accompanied its electric arc furnace with another plant making direct reduced iron (indeed, this is what unions are urging it to do). British Steel at Scunthorpe could be engaging with the nearby hubs to become a genuine contender in making carbon capture work.

For me, the most depressing thing about what’s happening here isn’t the complaints you mostly hear about our steel strategy - that we are becoming more dependent on imports or consigning ourselves to steelmaking technology which cannot produce all grades. As you’ve read above, neither of those complaints truly stack up.

No, the most depressing thing is that the country of Darby and Bessemer, the country which invented the Industrial Revolution, seems to lack the imagination and ambition to participate in the next one.

Closing the UK's blast furnaces doesn't change the quantity of scrap steel that is available worldwide for making of steel in an EAF, nor does it change the quantity of virgin steel that must be produced worldwide to make up the difference between world demand for steel and world supply of scrap.

It therefore does not change the world production of blast furnace steel, and by implication it has no impact on the world's CO2 emissions except that it moves those emissions from the UK to somewhere else, probably China.

It is greenwashing by deindustrialization, and it's one of the reasons why the west's futile attempts at decarbonization are having minimal impact on world CO2 emissions.

Interesting as always. Learned a new word: psephology - the statistical study of elections and trends in voting