America still needs Canadian oil. Here's why

And why the tariffs on Canada could plausibly lead to America doing deals with considerably more shady countries. A dive into the weird and wonderful world of heavy oil

As Donald Trump wages trade war against his nearest economic neighbours and biggest trade partners, there is one small but significant detail we should briefly ponder. What is the main thing the US actually imports from Canada? No, it’s not fentanyl. It’s crude oil.

I realise dwelling on this might seem a little like a sideshow in the face of the extraordinary events of recent days, but I promise this is worth contemplating. In part because it’s actually rather interesting and counterintuitive. And in part because, well, if you follow this thread far enough, it leads to even more unsettling conclusions.

Now, on the face of it, it’s actually a little odd that America is quite so reliant on Canada for its oil. After all, as is by now quite widely understood, these days the US is a massive oil producer - the biggest in the world. The biggest of all time, even. This is a consequence of the shale oil revolution - arguably the most underrated economic story of the past 50 years.

Having bewailed its enormous energy deficit for decades, America now produces far more oil than it consumes, making it a net petroleum exporter. Yet it continues to suck in vast quantities of Canadian crude.

Indeed, that reliance on Canadian oil has only grown in recent years. Look: right now, Canada accounts for a staggering 61 per cent of all imported oil to the US. That’s a pretty extraordinary degree of reliance (and explains why one of the few concessions the White House has made on the headline 25% tariff rate was for oil, which will face a lower but still significant tariff of 10%).

This outsized reliance on Canada is, it’s worth adding, a relatively recent thing: at the start of Donald Trump’s first term in office, America was importing about the same amount of oil from OPEC members, primarily in the Middle East, as it was from Canada. Up until the imposition of these tariffs, America’s energy story was becoming considerably more North American. Considerably more Canadian. So: why’s this happening?

For the answer, the best place to look isn’t economics textbooks but somewhere else: look instead at the crude oil itself. I mean, literally look at the crude.

Canadian oil is thick and gloopy. Much of it comes from tar sands and some comes from viscous deposits in the middle of the country. It doesn’t gush; it oozes, a viscous, black substance that’s somewhere between liquid and solid.

The technical term for this kind of oil is heavy oil. It takes considerably more work - more processes and technology - to refine. It’s not easy. And many of the breakthroughs in how you take this heavy oil and refine it into petroleum, kerosene and other products happened in the US, since Californian crude was mostly heavy stuff.

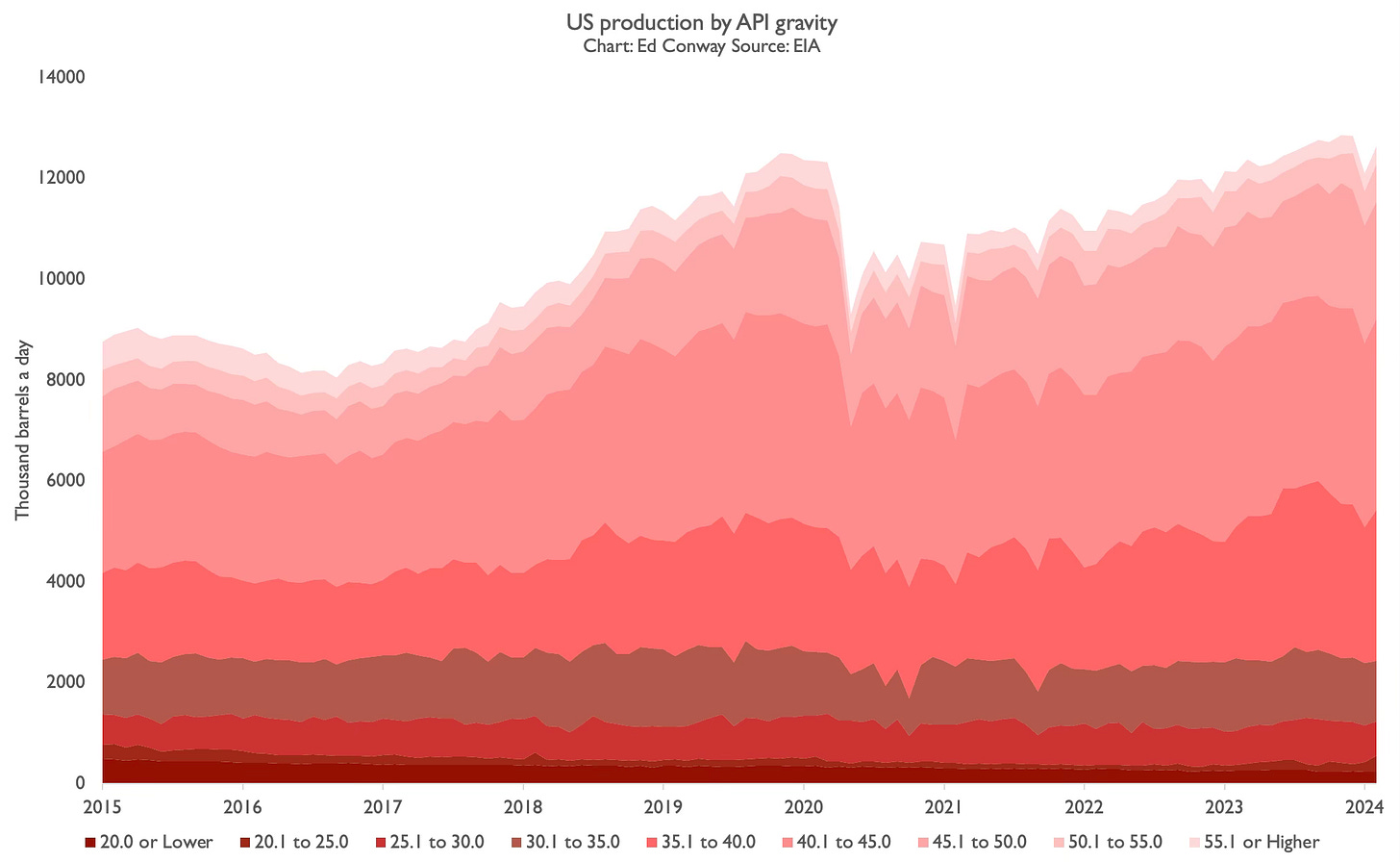

And since this has long been America’s expertise and since America has long been surrounded by supplies of heavy oil - in California, Canada and Venezuela - most American refineries have tended to specialise in heavy oil. This specialisation has actually intensified in recent years: look at crude imports to the US broken down by how heavy they are (the unit of weight of oil is known as API Gravity, and the lower that number is, the heavier the oil).

Look at how the darker segments of the chart have become the dominant type of import in recent years. That’s heavy oil. And, yes, most of it comes from Canada. But crude comes in many different thousands of different flavours and varieties, each one a product of the geological and organic processes which formed it over millions of years. As I wrote in Material World:

Most American refineries are set up for the kinds of heavy, sour crudes you get from Canada, Mexico and Venezuela. That made sense when it looked as if the US was running out of domestic oil, but then came the shale oil revolution. American shale oil, it turns out, is typically light and high quality, meaning it is not best-suited for domestic refineries. The upshot is that while arithmetically America is energy independent – producing far more oil than it consumes – in practice it is anything but. It must keep sucking in heavy oils from elsewhere to feed its refineries while sending Texan crude off to Europe and Asia to be refined.

Here, courtesy of this fascinating piece from Business Insider is what some shale oil from the Dakotas looks like.

Not only is it a lighter colour than the black stuff in Canada, it’s far less viscous too. It flows more like water. And since light oil is usually much purer when it comes out of the ground, it’s very different to refine. You don’t need all the clever technologies they have in American refineries. Indeed, American refineries simply aren’t equipped to deal with oils with an API gravity lighter than 30. And it turns out this is most of the stuff coming out of the US right now.

There’s a crucial irony here. While, statistically at least, the US is energy independent, producing far more crude oil than it needs, the variety of crude it produces isn’t compatible with its refineries, and hence it gets shipped off elsewhere and the US remains reliant on the rest of the world for that heavy oil.

Now, in the long run it’s not unfeasible that the US could begin to refit its refineries so they’re compatible with domestic shale oil. But up until now no-one thought that was worth doing because a) it’s very expensive b) it would take a long time and c) anyway, the US industry makes comparatively more money today from importing comparatively cheap oil (the heavy stuff sells for less) and selling their expensive, light oil overseas.

So, in the short run at least, the US will remain dependent on thick, gloopy heavy oil from elsewhere around the world. And since Donald Trump has decided to put 10% tariffs on Canadian heavy oil, the thick gloopy oil is about to become considerably more expensive which, all else equal, will push up gasoline prices pretty quickly.

Casts your mind ahead (no easy task these days), and you can probably imagine at least a couple of possibilities. The first is that the trade war ends about as quickly as it began. That, after all, was what happened with Colombia the other week. But what if it doesn’t? What happens if US refineries need to look elsewhere for their heavy, gloopy oil?

Here’s where things get, well, a little ominous. Because it turns out actually there aren’t all that many countries out there producing enormous amounts of heavy oil. There’s a bit of it in the Gulf - but most of the stuff coming out of Saudi, for instance, is too light for US refineries. There’s a few heavy oil fields in the North Sea (including the controversial Cambo field). But other than Canada, there are really only two other serious contenders for heavy oil production worldwide. Have a look:

That’s right: it’s Venezuela, or… Russia.

All of which is to say, the logic of Donald Trump’s plan to slap tariffs on the democracy directly to the north might well be to send him into the arms of two not-exactly-democracies. Raising another question: is it just a coincidence that the president has authorised a hostage handover with Venezuela? Come to mention it: what does this all spell for negotiations with Vladimir Putin over Ukraine?

All rather unsettling. And a reminder that often it’s quite enlightening to look at the world not from the top down, but from the vantage point of the materials we need for civilisation.

You could not write an article like this without a foundation in geography, a discipline which connects the physical world to the economic, political and social. Understanding These interconnections are what make this analysis so compelling

Canadians tend to decry the fact that we are both an importer and exporter of crude oil, but this is due to the fact that our refineries in Eastern Canada are equipped to handle light and sweet crude oil, while our oil produced in the West is heavy and sour. Despite existing pipelines which are fully capable of bringing oil from the West to the East, the current arrangement of sending Albertan oil to the United States, while Eastern refineries import oil from abroad, is more economical than adapting our refineries. In a world with a volatile neighbour as we have now, the solution is to develop our refining capacity in the West. Insulating our energy industry seems to be more important than ever, both economically and as a nation-building exercise in the face of threats of annexation, however serious.