A dying industry dies a bit more

How did one of the world's most cost-competitive plants become unsustainable in only a couple of decades? Here's what happened to the ethylene cracker at Wilton - and one or two wider lessons

Once upon a time, there were few industrial sites quite as, well, industrial as the chemicals plant on the banks of the River Tees.

There on the north bank at Billingham was the Haber-Bosch fertiliser unit which was helping feed the world (not to mention developing the technology that most other fertiliser plants around the world would end up adopting). There was a plant making the chemicals used to make things like perspex. Indeed, the perspex that went into Spitfire canopies came from here.

Off on the south bank, out on the coast, were the tall towers of the blast furnaces, belching smoke into the sky and the convertors forging the steel that would help Middlesbrough construct the world. Alongside it, on the Wilton site, was a forest of chimneys belonging to countless different units. This was where Teesside made the polyester that clothed the world (a British invention, don’t you know).

There were power stations and polyurethane plants, as well as the ethylene crackers: high-pressure steel containers for the chemical reaction that turned North Sea oil into ethylene - the precursor to the most important plastic in the world, polyethylene (another British invention).

These materials, many of them still made in Britain until surprisingly recently, represent part of the backbone of the modern world. Yes, there’s countless other important innovations that have happened since, but the whole point of my writing Material World was to say: we don’t talk about this stuff enough, and it still matters.

The fact that polyethylene was invented here in Britain provided the allies with a decisive edge in WWII, since it was used to shield the wires that enabled British planes to have airborne radar. This lightweight material indirectly saved countless lives. But this plastic is also the backbone of the modern world too. It goes into packaging that helps keep pharmaceuticals and foods clean. It goes into water pipes and bubble wrap, into hip replacements and flak jackets. As I wrote in the book, “every six seconds we make enough of it in Europe to wrap the Eiffel Tower from head to toe.”

As you know, there is and was a dark side to this too. We waste far too much plastic and chuck too much of it away into rivers and the seas, where it can play havoc with ecosystems. The plants here were sometimes desperately dirty - especially back before the more stringent environmental regulations were put into place. One of the brooks that fed the Tees here was, for a period, famous for being the most toxic river in the country.

So it is quite hard when you visit Wilton these days, as I did when I was researching Material World a few years ago, to reconcile what you see there today with what once was. As you will recall if you read the book, I was spending a moment staring at that one-time famously toxic river when, all of a sudden, a seal popped its head out of the water and stared us in the face. In all the time we spent driving around there, I saw not a single human being.

In part this owes itself to the fact that by the time I visited, much of the plant had been shut down and was empty. The polyester plant had gone. The steel works were in the process of being disassembled. But that emptiness was also a little deceptive. These days, for better or worse, you don’t need many humans to run a plant producing millions of tonnes of product (we’ll come back to this later). So back then, the fertiliser plant was still running, as was the place which used to produce the precursors for perspex. And the ethylene cracker was still flaring away into the Teesside sky.

“Not a lot of people know that most of Europe’s plastic bags begin their life here in Teesside,” said the fellow who was showing me around. “But they still do. Not that anyone wants to talk about it.”

Well, not any more. Because Sabic, the company that operates the ethylene cracker at Wilton, has just announced that it will be closing. On the surface, this is, in the grand span of Britain’s story of deindustrialisation, a relatively small chapter. The demise of a plant most people haven’t heard of, run by a company most people haven’t heard of, making a product most people haven’t heard of (even if they use it every day), resulting in the loss of around 100 jobs.

But the problem is: this is far from an isolated case. And the sorry story of Wilton is something we should all be aware of. Indeed, in some senses, the demise of this place is just as if not more significant than the near-collapse of British Steel, an episode that hogged the headlines for weeks, and eventuated in the government essentially nationalising the company.

So… why does British Steel get a bailout while this place dies a quiet death? I have a pet theory.

The end of ICI

This theory begins in the mid 1990s. Back then, nearly all of the units here were owned and run by a single company: Imperial Chemicals Industry.

ICI was one of the most important companies in the world, one of the biggest employers in the country. It was so important and influential that it dominated the corporate conversation in the country. Its massive headquarters on the banks of the River Thames - just down Millbank from Parliament - were arguably the real power centre for UK plc. Together with its continental counterpart BASF and American firms like Dupont, ICI was one of the giants of global industry.

But it disintegrated in somewhat catastrophic circumstances in the 1990s, selling off vast parts of its estates. All of a sudden, Britain’s chemicals industry was split into countless pieces. Much of ICI still lives on today, in a different guise. Much of the pharmaceutical bits (eventually) became AstraZeneca. Parts of the salt-related chemicals business were eventually acquired by Indian group Tata. Much of the basic chemicals business was bought by Jim Ratcliffe and became Ineos. But even this is an over-simplification.

It’s worth saying that while it’s tempting to see ICI’s implosion, and the later closure of various bits of the diaspora, as an indictment of the quality of Britain’s chemicals industry, this really couldn’t be further from the truth. Take the ethylene cracker at Wilton - the one that’s just shut down. Back when ICI sold it in 1999 to American chemicals firm Huntsman, it was one of the lowest cost crackers in the world. That might sound bonkers these days, but it’s really true. It was cheaper to make ethylene on Teesside than it was to make it in most of Asia and the US!

In part that was because it was a pretty advanced, efficient plant - and a big one at that. And in part it was because it was fed, via pipeline, with cheap oil from the Ekofisk oil and gas fields in the North Sea. Even in the aftermath of ICI’s collapse, things looked bright for Britain’s chemicals industry - still one of the world’s leaders. And since the world’s appetite for polyethylene was rising exponentially, there was no reason to suspect that, in only a couple of decades, the site would face its effective demise.

So: what went wrong? Well, that alone is the subject of an entire book, but here, off the top of my head, are a few contributory factors to bear in mind.

First, North Sea oil output peaked and fell. Gradually, it became clear that there was more oil more easily available elsewhere - most notably in the US, thanks to the shale revolution. Second, Asian competitors, which had struggled up until the 2010s to build their own ethylene plants, learnt the technology. Soon enough there were crackers on the other side of the world competing and beating Teesside on price. Third, Europe began to impose growing regulations on big polluters like the chemicals industry.

Hypothesising that the future of the region might be not in old fashioned oil and gas-based chemicals but in cleaner, newer technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen, the UK government encouraged firms to invest in this new hydrogen economy. By then, Huntsman had sold the cracker to Sabic, which saw Wilton as their “green” play. As the world shifted to “blue” and then “green” hydrogen, these crackers would be perfectly placed to benefit from the new green economy.

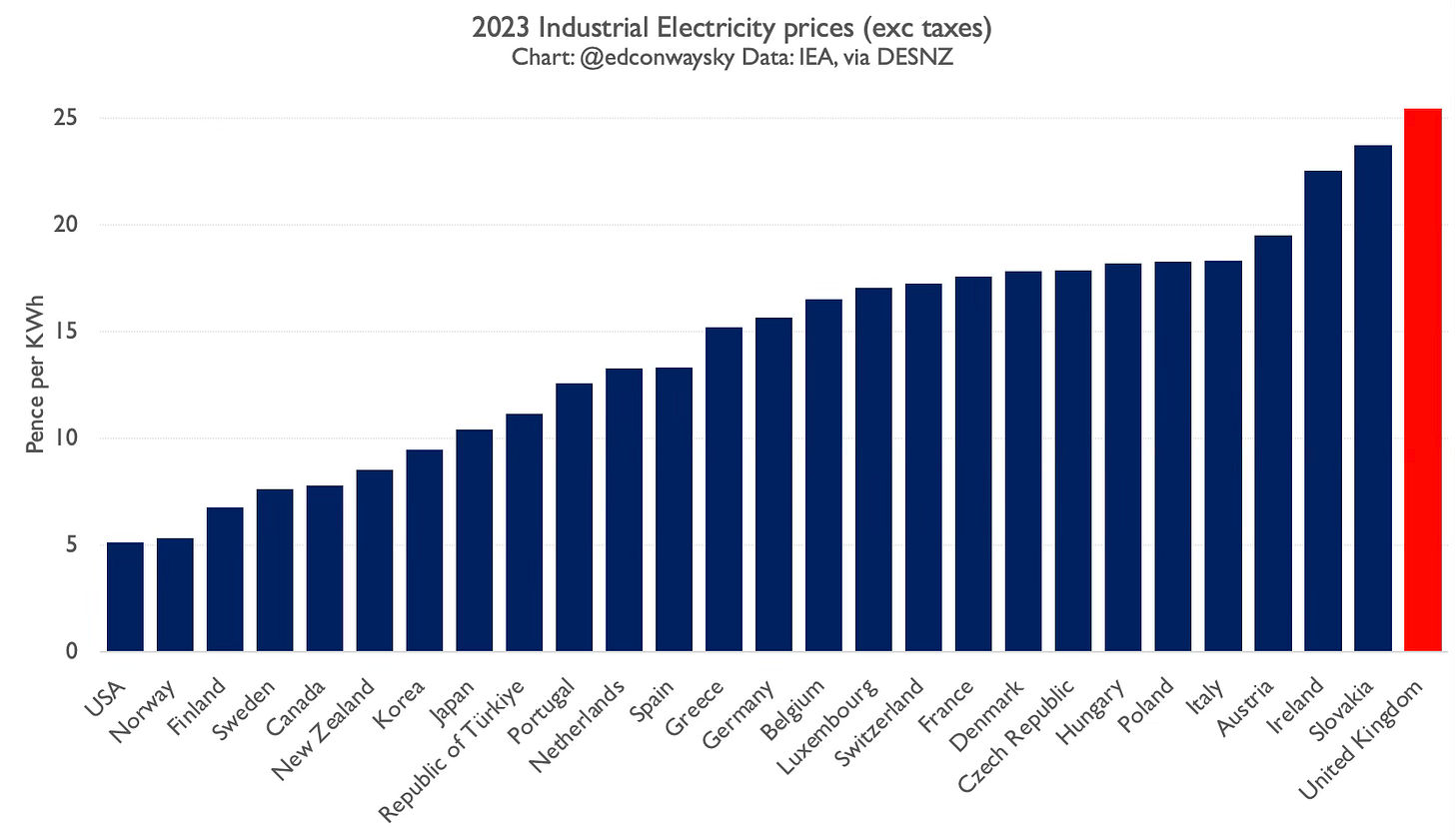

In the meantime, energy prices into the UK went from being among the lowest in Europe to among the highest in the developed world. The hydrogen economy remained what it was back a decade ago - which is to say, a lovely idea but, in practice, way too expensive to compete with old fashioned chemicals and energy. And, first gradually and then suddenly, Wilton was out of business. British ethylene could no longer compete - to the extent that even wealthy, patient firms like Sabic (an offshoot of the Saudi government) could no longer justify the losses.

All of which is to say, the announcement of its closure today is far from surprising. It has been coming for years, the consequence of a series of unfortunate events and poor decisions.

But don’t take from that that this was altogether inevitable.

What would have happened if ICI had never fallen to pieces in the 1990s? Would government have paid more attention if the firm shutting down was a household name rather than an obscure Saudi-owned group?

To what extent is the implosion of the chemicals sector more broadly a consequence of the fact that each chemicals plant doesn’t employ as many people as a single steelworks - even though their broader contribution to GDP is significant? Allowing a steelworks like Scunthorpe to close down, with the loss of, maybe 2,000 jobs overnight, is seen in Whitehall as politically unpalatable. But right now chemicals plants are closing with astounding regularity - 100 jobs a time. It all adds up eventually - perhaps to more job losses than would have happened at British Steel. But it’s death by a thousand cuts - and so it doesn’t reach the threshold at which Westminster sits up and pays attention.

More widely, what would have happened had more attention been paid to galloping energy costs a few years ago rather than today? One of the points I made in the book was that part of the problem facing British industry in recent years is that they have had to bear most of the extra green levies on their power bills, while countries like Germany imposed most of those costs on households instead. One of the key planks of the Industrial Strategy document released earlier this week is that those costs will no longer be borne by industrial energy users. But this is hardly a new issue: why did it take so long to change?

Either way, the reality is that Wilton doesn’t now just feel empty; increasingly, it is empty. A site that felt pretty desolate when I visited a few years ago is now almost deserted. A part of the country that was supposed to be “levelled up”, as the previous government put it, is now being levelled.

And Britain is becoming ever more dependent on other countries for the chemicals it uses for everything from pharmaceuticals to weapons to fertilisers. That’s unprecedented. And is something we should all spend some time pondering.

My father worked at ICI Wilton in 1970's. Back then every kid in my school's father worked either at ICI or Teesside Steelworks-75,000 employees all told. I recall ICI shareholders seeking to release value was one of the major causes of the company break-up but your analysis is spot on. Sadly, associated jobs now in the hundreds.

Nice text. There are some technical details missing. China makes ethylene from ethane (natural gas). So much that it have to lower down retaliatory tariffs on US ethane, otherwise the plastic industry collapsed. UK cannot do the same?. They can even buy natural gas from some technical ignorant (or capital/technology strapped) countries like my own: Argentina, which sell the raw natural gas, including ethane and propane. Use the methane or energy and the rest for more pricey olefins. With respect to energy prices, if you impose your industry high energy price because of climate change, you should apply a tariff on any product made with cheap non green (coal) energy. Last time I check, the CO2 emitted in China is the same than in the UK. Or you are just a fool